Artificial intelligence is often described as neutral, technical, and universal. Algorithms, data, and machine learning models are often portrayed as tools that behave consistently regardless of their deployment location. Yet new research suggests that this assumption is deeply flawed. Artificial intelligence does not simply process data. It absorbs social values, political histories and institutional logics from the environments in which it is developed.

A recent study by Qiaoyu Cai from the University of California, Santa Barbara, published in the journal Theory, Culture & Society, challenges prevailing Western narratives about AI by examining how artificial intelligence develops within China’s distinct political and cultural context. Titled The Cultural Politics of Artificial Intelligence in China, the article argues that Chinese AI cannot be fully understood through dominant frameworks such as neoliberalism, surveillance capitalism or state capitalism alone.

Instead, Cai introduces the concept of postsocialist AI, a form of artificial intelligence shaped by the ongoing interaction between market forces, state power and socialist political legacies. The study presents an important contribution to global AI research, raising questions about how political systems influence machine intelligence itself and why assumptions drawn from Western liberal democracies may fail to explain AI development in other contexts.

A smart city that thinks differently

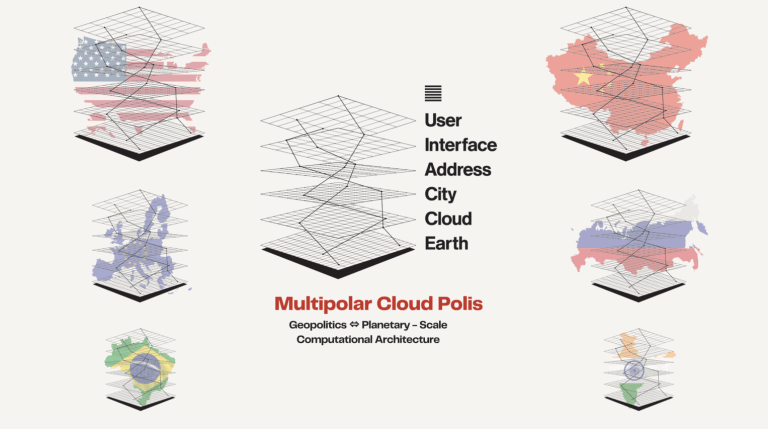

One of the most prominent examples discussed in the research is City Brain, an AI-driven urban governance platform developed by Alibaba. Now deployed in more than 20 Chinese cities and exported internationally, City Brain integrates data from traffic systems, healthcare services, public security networks, and environmental monitoring to support real-time urban decision-making.

From a technical perspective, City Brain resembles smart city projects in Europe and North America. It relies on big data analytics, deep learning models and predictive algorithms. However, Cai’s analysis shows that its political logic differs in fundamental ways.

In Western smart city discourse, civic engagement is usually framed around individual rights, transparency and legal accountability. In China, by contrast, policy documents and corporate white papers repeatedly emphasise grassroots governance. This language reflects Maoist political traditions in which the state claims legitimacy by remaining embedded within local communities while maintaining centralised authority.

City Brain, therefore, operates within a governance model that blends market-driven innovation with Leninist Maoist institutional structures. Private companies provide technical expertise, but strategic direction remains in the hands of the state. This produces a system that is neither purely capitalist nor fully socialist, but something more complex and historically specific.

Beyond the myth of a global AI race

Much public discussion about Chinese artificial intelligence is framed through the language of competition. Media narratives often describe an AI race or AI cold war between China and the United States, implying that both countries are pursuing similar technological goals through different political systems.

Cai’s research complicates this picture. While China’s national AI development plans emphasize economic growth, technological leadership and national security, they largely avoid articulating a political vision of what AI should mean for social life. This absence, Cai argues, reflects a broader trend of depoliticized developmentalism in which economic performance is prioritized over democratic deliberation or social justice.

Yet unlike neoliberal governance models in the West, China’s approach is shaped by a lingering commitment to socialist ideals such as collective welfare and popular sovereignty. These ideals remain powerful at the level of political discourse, even when they conflict with market-driven outcomes in practice.

The state and capital as co-architects of AI

Central to Cai’s argument is the idea of a state capital nexus. Artificial intelligence is one of the most capital-intensive technological projects of the twenty-first century, requiring massive investments in infrastructure, data collection, and computational resources. As a result, states play a central role in shaping AI development everywhere, including in liberal democracies.

What distinguishes China is not state involvement per se, but the structure of that involvement. Rather than allowing corporations to dominate urban AI projects, Chinese authorities often retain significant leverage through public ownership, regulatory power, and decentralised governance mechanisms.

Local governments are granted autonomy to experiment with AI systems tailored to regional priorities. At the same time, national agencies establish overarching policy frameworks and evaluation metrics. This creates a system of centralised command combined with decentralised execution, enabling rapid experimentation while maintaining political control.

Cai argues that this experimentalist governance model reflects a continuation of socialist administrative traditions rather than a simple adoption of neoliberal practices. It also shapes how AI systems are trained, deployed and evaluated within Chinese cities.

When machines learn from society

One of the most distinctive contributions of the study lies in its analysis of machine learning as a social process. Modern AI systems do not simply execute predefined instructions. Through supervised, self-supervised, and unsupervised learning, they develop patterns of reasoning based on continuous interaction with their environments.

This process, described as the ontogenesis or sociogenesis of machine learning, means that AI systems internalise social norms, institutional priorities and political assumptions embedded in their training data. In China’s case, this includes a governance culture that prioritises collective stability, administrative efficiency, and state authority.

Cai draws on the concept of technical mentality developed by philosopher Gilbert Simondon to argue that machine intelligence exhibits a form of agency shaped by its sociopolitical context. AI systems do not merely reflect human intentions. They generate their own forms of knowledge and decision-making, informed by the values encoded in their operational environments.

This perspective challenges dominant assumptions in AI ethics, which often focus on individual bias or corporate responsibility while neglecting broader political structures.

Challenging homo economicus in AI studies

Much Western AI research implicitly assumes that artificial intelligence is shaped by homo economicus, the neoliberal figure of the rational, profit-maximising individual. Under this framework, AI systems are designed to optimise efficiency, productivity, and economic growth above all else.

Cai argues that this assumption obscures alternative political subjectivities. In the Chinese postsocialist context, the dominant epistemic figure is not homo economicus but what Cai describes as homo politicus postsocialismus, a subject shaped by collective political identity, historical consciousness, and state-mediated participation.

This does not mean that Chinese AI is more democratic or less coercive. On the contrary, the study acknowledges serious ethical concerns surrounding surveillance, data governance and authoritarian control. However, these issues cannot be fully understood using analytical categories developed exclusively within Western liberal traditions.

Examining AI development in China requires neither objectifying AI nor objectifying China but attending to the interactive encounter between the ‘alien dimension’ of algorithmic thought and a distinctly Chinese experience of modernity – both of which remain unassimilable to the global reproduction of neoliberal subjectivity.

-Qiaoyu Cai

Surveillance capitalism or surveillance statism

Western critiques of Chinese AI often rely on the concept of surveillance capitalism, popularised by Shoshana Zuboff. This framework emphasises the role of private corporations in extracting behavioural data for profit, thereby undermining individual autonomy.

Cai suggests that this model does not adequately describe the Chinese case. In China, data governance is dominated by the state rather than private firms. Surveillance practices are integrated into political administration rather than driven primarily by market incentives.

This distinction has important implications. While surveillance capitalism focuses on consumer exploitation, China’s model resembles what Cai describes as surveillance statism, in which data collection serves governance objectives such as social stability, policy enforcement and administrative coordination.

Understanding this difference is crucial for engaging in meaningful global debates about AI ethics, data governance, and digital sovereignty.

Reference

Cai, Q. 2025. The cultural politics of artificial intelligence in China. Theory, Culture & Society, 42(3), 21 to 40. https://doi.org/10.1177/02632764241304718