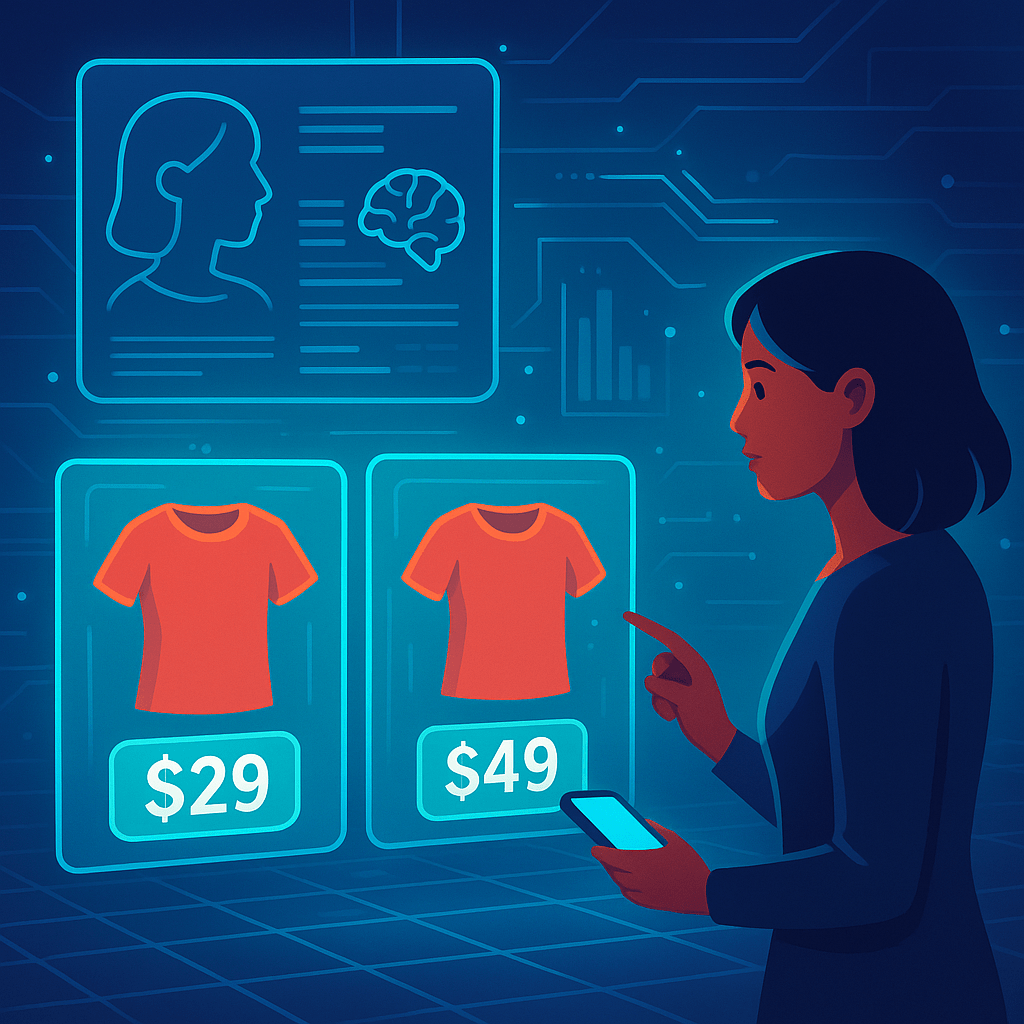

When two people see different prices for the same pair of headphones or hotel room online, it is not a computer glitch. It is the outcome of personalised pricing, a data-driven strategy where algorithms predict how much each consumer is willing to pay. Advocates argue that this system increases efficiency and overall welfare. Yet new research led by Dr Deni Mazrekaj of Utrecht University questions whether this increasingly common practice is as ethical as it seems.

In a study published in the Journal of Business Ethics, titled Does Price Personalization Ethically Outperform Unitary Pricing? A Thought Experiment and a Simulation Study, Mazrekaj and colleagues re-examine a popular claim in business ethics: that charging individuals different prices can sometimes be fairer than charging everyone the same amount. Their findings reveal a far more nuanced ethical landscape, one shaped not only by economics but also by perceptions of fairness, privacy, and trust in digital markets.

The promise of personalised pricing

Technological advances have given firms the power to tailor prices according to personal characteristics, spending history, and even browsing behaviour. Retailers, streaming services and ride-hailing platforms increasingly rely on algorithmic models to estimate each customer’s willingness to pay. In theory, this practice maximises both profits and accessibility: wealthier consumers may pay slightly more, subsidising access for those with lower incomes.

Earlier ethical analyses suggested that personalised pricing outperforms traditional or unitary pricing, where everyone pays the same amount, when judged through several consequentialist social welfare functions. These frameworks, including utilitarianism, egalitarianism, prioritarianism, and leximin, evaluate the impact of pricing strategies on total welfare and equality across society. According to that earlier model, differential pricing could make markets fairer by aligning price with individual utility.

Yet Mazrekaj’s team found that this conclusion depends on highly specific assumptions. Once they introduced realistic psychological and behavioural costs into the model, the ethical superiority of personalised pricing began to collapse.

The ethics of perception

Mazrekaj and his co-authors, Mark D. Verhagen (University of Oxford), Ajay Kumar (EMLYON Business School), and Daniel Muzio (University of York), extended the earlier framework to include two new sources of disutility: unfairness perception and surveillance aversion. These additions recognise that consumers are not purely rational actors. They respond emotionally to how they are treated, and these responses carry ethical weight.

Unfairness perception refers to the sense of being wronged when one discovers that another consumer paid less for the same product. Surveys in the United States show that more than 70 per cent of respondents view such price discrepancies as unfair or manipulative, even if they personally benefit from them.

Surveillance aversion refers to the discomfort people experience when companies track and use their personal data for pricing decisions. As digital commerce expands, consumers are increasingly concerned that they are being monitored. This perception of constant observation, often referred to as digital surveillance, can lead to a measurable decline in well-being. Even with privacy regulations such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), people remain uneasy about how their data is used, and that discomfort translates into ethical costs.

Modelling ethics with mathematics

The study reconstructs a simplified market scenario inspired by Coker and Izaret’s earlier model, featuring two consumers, Alice and Bob, who each consider subscribing to The Business Journal. Alice earns ten times more than Bob and gains slightly greater utility from the product. Under unitary pricing, both would pay £20. Under personalised pricing, algorithms estimate their willingness to pay and charge Alice £35 and Bob £5.

Mazrekaj’s simulation introduced additional parameters to quantify disutility from unfairness and surveillance. These components were treated as small percentages of the utility gained from the purchase. Even when these psychological costs were set at conservative levels, just five per cent of the product’s perceived benefit, the ethical balance shifted dramatically.

Under utilitarian and prioritarian frameworks, which value total welfare and the well-being of the least advantaged, respectively, unitary pricing consistently outperformed personalised pricing once these disutilities were included. Only when equality was prioritised above total welfare, as in egalitarian and leximin ethics, did personalised pricing retain an ethical advantage, and even then at the expense of overall happiness.

When fairness outweighs efficiency

The researchers conclude that the ethical appeal of personalised pricing collapses when fairness and privacy enter the equation. Small emotional costs can outweigh the theoretical efficiency gains predicted by economics.

In practice, this means that if consumers believe they are being unfairly treated or watched too closely, even marginal discomfort can make uniform pricing ethically superior. “Unfairness perception and surveillance aversion directly erode utility,” the authors note, “and because personalised pricing already yields modest welfare improvements, these small losses are sufficient to reverse the outcome.”

Importantly, the model does not suggest that personalised pricing is always unethical. In cases where the alternative would be no product at all, such as healthcare in low-income settings or rare disease medications that require variable pricing to remain viable, differentiated pricing may still increase welfare. However, for most everyday markets, where products would exist regardless of pricing strategy, uniform prices may generate greater ethical value.

Algorithms, consumers and the illusion of choice

The paper’s findings also speak to broader debates about algorithmic ethics and AI in pricing. Algorithms may appear neutral, yet they can embed social biases by using data that reflects existing inequalities. Consumers may be segmented by income, geography, or even the type of device used to access a website. Studies have shown that users booking hotels on Apple computers were once quoted higher prices than those on Windows machines.

Such practices challenge the principle of equal treatment in market exchange. They also create a paradox of transparency: companies are expected to disclose their pricing algorithms, but doing so risks heightening consumer anxiety and backlash. The authors argue that transparency alone cannot eliminate feelings of unfairness, since the very knowledge of being priced differently can generate disutility.

The ethical challenge of personalised pricing is not whether firms can charge different prices, but whether they should.

– Deni Mazrekaj

The role of regulation and social norms

The research highlights a crucial intersection between ethics and policy. Privacy laws such as the GDPR in Europe or the California Consumer Privacy Act in the United States compel companies to inform users about data collection and personalised pricing. Yet awareness does not necessarily mitigate discomfort. Many people ignore consent notices or fail to understand how their information is used.

Mazrekaj’s analysis implies that even fully compliant companies may face ethical challenges if consumers feel exploited. Over time, social norms may evolve: what is considered manipulative today might be seen as acceptable tomorrow, just as dynamic airline pricing became normalised after initial resistance. However, this shift will likely be gradual and uneven across cultures and markets.

Implications for businesses and consumers

Personalised pricing might maximise profits in the short term, but it risks damaging long-term trust and brand reputation. Firms that rely on algorithmic price differentiation must strike a balance between profitability, transparency, and consumer welfare. Explicit communication about how prices are determined, or allowing customers to opt out of data-driven pricing, could mitigate some ethical concerns.

For consumers, the findings invite greater awareness of digital trade-offs. Convenience and customisation often come at the cost of privacy. As personalised pricing spreads across e-commerce, entertainment, and transport sectors, individuals may need to weigh the benefits of tailored offers against the discomfort of constant surveillance.

The authors conclude that unitary pricing can ethically outperform personalised pricing under most real-world conditions, especially when even minor psychological costs are considered. Personalised pricing only prevails under ethical systems that value equality over total welfare, and even then, its moral advantage is fragile.

Reference

Mazrekaj, D., Verhagen, M. D., Kumar, A., & Muzio, D. (2025). Does Price Personalization Ethically Outperform Unitary Pricing? A Thought Experiment and a Simulation Study. Journal of Business Ethics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-024-05828-3