Brain tumours and brain metastases continue to represent one of the most formidable challenges in modern oncology. While advances in targeted cancer therapies have transformed outcomes for many solid tumours, these benefits often disappear once cancer spreads to the brain. The primary reason is not a lack of effective drugs, but the presence of the blood-brain barrier, a highly selective interface that tightly regulates what enters the brain from the bloodstream.

This biological safeguard protects neural tissue from toxins and pathogens, but it also blocks most therapeutic molecules, including monoclonal antibodies and many chemotherapeutic agents. As a result, patients with brain metastases frequently face limited treatment options and poor survival outcomes. Triple negative breast cancer, in particular, is notorious for its aggressive behaviour and high rate of brain involvement, often leaving clinicians with few effective interventions.

A new study published in Nature Nanotechnology offers a compelling and unexpected solution.

A study that challenges long-held assumptions

The research article, titled “Systemic HER3 ligand mimicking nanobioparticles enter the brain and reduce intracranial tumour growth”, was led by first author Felix Alonso Valenteen and published in May 2025 in Nature Nanotechnology. The work was conducted at Cedars Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, with contributions from multidisciplinary teams spanning nanotechnology, cancer biology and neuroscience.

At the heart of the study is a simple but powerful observation. When the research team administered specially engineered nanobiological particle systems in animal models, these particles were detected in the brain even in the absence of tumours. This finding challenged the prevailing assumption that the blood-brain barrier becomes permeable only when tumours are present and instead pointed to an active, receptor-mediated transport mechanism.

Rather than forcing drugs across the barrier, the researchers discovered that they could exploit an existing biological pathway.

The blood-brain barrier is not just a wall

Traditionally, the blood-brain barrier has been described as an impenetrable wall formed by tightly joined endothelial cells lining brain blood vessels. While structurally accurate, this description overlooks the dynamic nature of the barrier. The barrier is not passive; it actively regulates molecular traffic through specialised receptors and transport systems.

The study reveals that one such receptor, the human epidermal growth factor receptor 3 (HER3), plays an unexpected role in this regulation. HER3 is widely recognised in cancer biology for its association with tumour growth, metastasis, and resistance to therapy. Elevated HER3 expression has been reported in breast cancer, glioblastoma, melanoma and several other malignancies, particularly those that spread to the brain.

What had not been fully appreciated until now is that HER3 is also prominently expressed on brain endothelial cells, positioning it as a potential gateway for systemic molecules to enter the brain.

Engineering particles that mimic nature

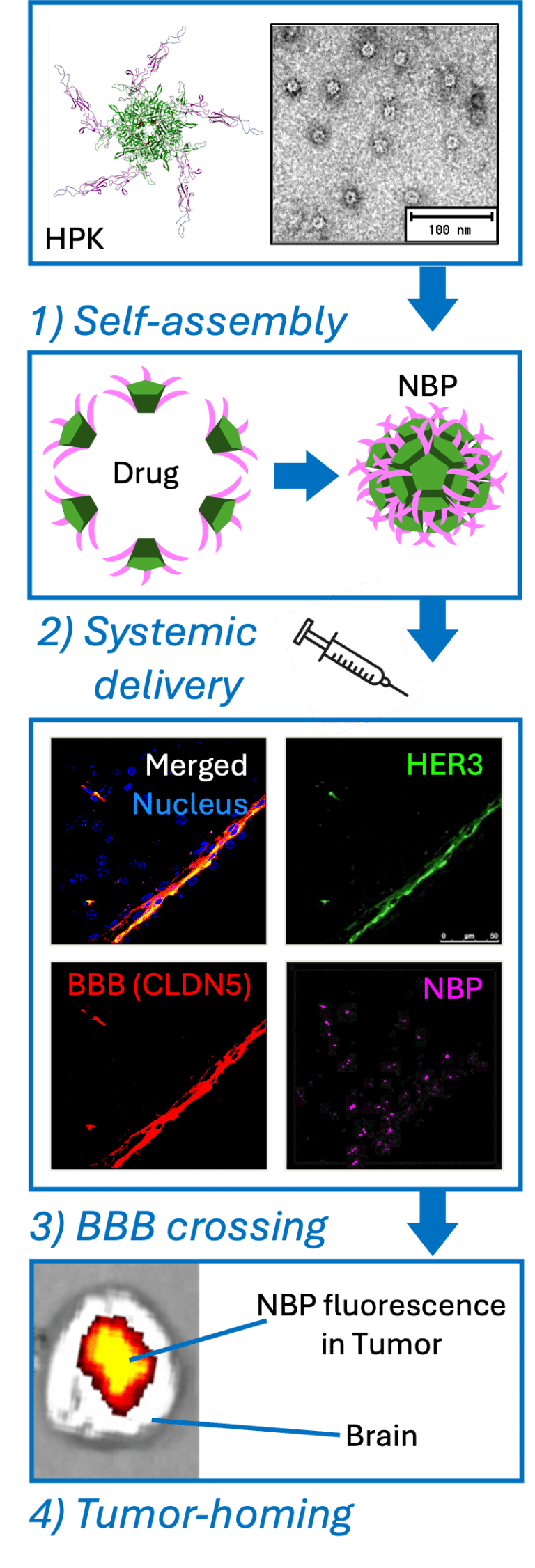

To take advantage of this pathway, the researchers designed nanobioparticles using a recombinant protein known as HPK. This protein incorporates a segment derived from neuregulin 1 alpha, the natural ligand for HER3, allowing it to bind specifically to HER3-expressing cells. It also contains structural elements derived from adenovirus capsid proteins, which enable it to self-assemble into nanoscale particles and disrupt endosomal membranes once inside cells.

These nanobioparticles are not passive carriers. They actively encapsulate therapeutic cargo, including nucleic acids and tumour toxic compounds, forming stable, spherical structures capable of protecting their payload during circulation. Importantly, the particles remain biologically compatible and show minimal immunogenicity in preclinical testing.

By mimicking a natural ligand rather than relying on antibodies, the particles avoid some of the limitations that have plagued antibody-based therapies in brain cancer, particularly their poor penetration across the blood-brain barrier.

From bloodstream to brain tissue

Using advanced imaging techniques and biodistribution studies in mice, the researchers demonstrated that systemically administered HER3-targeted nanobioparticles accumulated not only in peripheral tumours but also within brain tissue. This accumulation occurred without the need for mechanical or chemical disruption of the blood-brain barrier.

Further experiments using human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived blood-brain barrier chips confirmed that the particles crossed the endothelial layer via HER3-mediated transcytosis. The process was closely associated with caveolin 1, a protein involved in vesicular transport within endothelial cells, suggesting a caveolae-dependent mechanism rather than passive leakage.

Crucially, free therapeutic molecules lacking the nanobioparticle carrier failed to cross the barrier, underscoring the importance of the engineered delivery system.

Targeting tumours inside the brain

The most clinically relevant findings emerged from experiments involving intracranial tumour models. In mice implanted with triple-negative breast cancer cells in the brain, systemically delivered nanobioparticles preferentially accumulated within tumour regions rather than healthy brain tissue.

When loaded with tumour-killing agents such as doxorubicin or gallium-based corrole compounds, the particles significantly reduced tumour growth compared to standard treatments like liposomal doxorubicin. Importantly, this enhanced efficacy was accompanied by reduced systemic toxicity and improved overall health indicators in treated animals.

Magnetic resonance imaging and bioluminescence imaging confirmed that some animals receiving the nanobioparticle-based therapy showed minimal or no detectable tumor progression, a result rarely observed with conventional chemotherapy in this setting.

Why HER3 changes the rules

HER3 has long been considered a challenging therapeutic target due to its lack of intrinsic kinase activity, rendering many small-molecule inhibitors ineffective. This study reframes HER3 not as a signaling target but as a biological transporter.

By exploiting HER3’s natural role in ligand-mediated uptake and transcytosis, the researchers bypass the need to inhibit its signalling function altogether. Instead, HER3 becomes a molecular doorway through which therapeutic cargo can enter both tumour cells and the brain itself.

This approach may have broad implications beyond breast cancer. HER3 overexpression has been documented in prostate, lung, ovarian, and gastric cancers, many of which frequently metastasise to the brain. As a result, HER3-targeted nanobioparticles could represent a platform technology rather than a single disease solution.

Implications for brain cancer treatment

For clinicians and researchers, the findings point towards a future in which systemic therapies are no longer excluded from the brain by default. Rather than resorting to invasive procedures or non-specific radiation, it may become possible to deliver precision medicines directly to intracranial tumours using biologically guided transport mechanisms.

The study also challenges the notion that effective brain drug delivery requires compromising the integrity of the blood-brain barrier. By working with the barrier rather than against it, the approach preserves normal brain function while enabling targeted intervention.

From a translational perspective, the use of biologically derived components and the demonstration of safety in preclinical models strengthen the case for eventual clinical development.

What remains to be done

Despite its promise, the research remains at a preclinical stage. Human trials will be required to determine whether the safety and efficacy observed in animal models translate to patients. Questions also remain regarding long-term immune responses, optimal dosing strategies, and potential off-target effects in diverse patient populations.

Nevertheless, the work provides compelling proof of concept and a new framework for thinking about drug delivery to the brain. It suggests that the blood brain barrier is not an insurmountable obstacle, but a complex biological system that can be intelligently navigated.

Reference

Alonso Valenteen, F., Mikhael, S., Wang, H. Q., Sims, J., Taguiam, M., Teh, J., Sances, S., Wong, M., Miao, T., Srinivas, D., Gonzalez Almeyda, N., Cho, R. H., Sanchez, R., Nguyenle, K., Serrano, E., Ondatje, B., Benhaghnazar, R. L., Gray, H. B., Gross, Z., Yu, J., Svendsen, C. N., Abrol, R., and Medina Kauwe, L. K. (2025). Systemic HER3 ligand mimicking nanobioparticles enter the brain and reduce intracranial tumour growth. Nature Nanotechnology, 20, 683 to 696. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41565-025-01867-7