In medicine, law, and science, the pressure to make quick decisions is often intense. Doctors must choose a treatment, investigators must select a suspect, and scientists must commit to a theory. Yet history repeatedly shows that premature certainty can lead to serious errors, from misdiagnoses to wrongful convictions and delayed scientific breakthroughs.

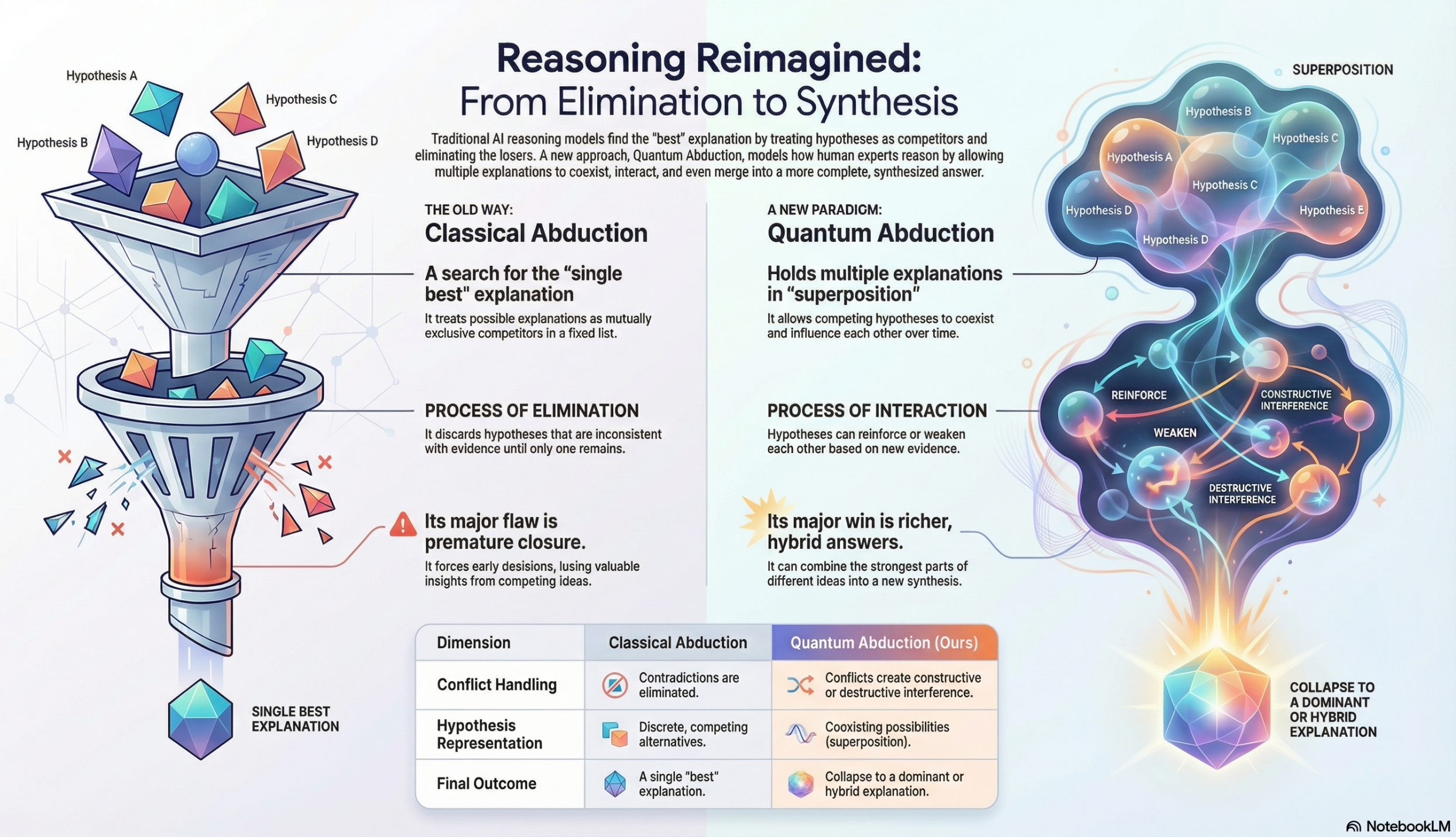

New research proposes that this tendency to eliminate possibilities too early is not a human flaw but a structural limitation of classical reasoning systems. Instead of forcing explanations to compete until only one survives, the research argues for a framework that allows multiple explanations to coexist, interact, and even strengthen one another before a final conclusion is reached.

This framework, known as quantum abduction, is introduced in a recent research by Remo Pareschi of the University of Molise, published in the journal Sci. The article, titled “Quantum Abduction: A New Paradigm for Reasoning Under Uncertainty”, offers a novel way to model how humans actually reason under ambiguity and how artificial intelligence (AI) systems might learn to do the same.

Why classical reasoning struggles with uncertainty

Abductive reasoning is the process of inferring the most plausible explanation from incomplete or uncertain evidence. It plays a central role in clinical diagnosis, criminal investigations, intelligence analysis, and scientific discovery. Traditionally, abductive reasoning systems treat explanations as mutually exclusive. Each hypothesis competes against the others, and evidence is used to eliminate weaker candidates until a single best explanation remains.

This eliminative approach works well in simple and well-structured environments. However, in complex real-world situations, evidence is often contradictory, incomplete, or context-dependent. In such cases, forcing early elimination can suppress valuable information and distort the reasoning process.

Pareschi argues that classical models fail on two time scales. In immediate decision contexts such as emergency medicine, experts rarely commit to a single explanation at once. Instead, they keep several diagnostic possibilities active until decisive tests are available. In long-term investigations such as scientific research or complex criminal cases, premature elimination can foster tunnel vision and institutional bias, preventing productive synthesis between competing theories.

The paper suggests that what appears irrational or indecisive is often a rational response to uncertainty. Human experts routinely tolerate contradiction and ambiguity because they understand that explanations can evolve as evidence accumulates.

In many complex decisions, the real mistake is not choosing the wrong explanation, but choosing too early.

-Remo Pareschi

A quantum-inspired model of explanation

Despite its name, quantum abduction does not claim that the brain operates according to quantum physics, nor does it rely on quantum computers. Instead, it borrows mathematical tools from quantum theory to model complex decision-making and problem-solving processes. It thus fits within the growing trend of quantum modeling, which involves using quantum principles to simulate and understand complex systems.

In this framework, hypotheses are represented as vectors in a high-dimensional semantic space. Rather than assigning a single probability to each explanation, the system maintains a superposition of explanatory states. Each hypothesis has an amplitude that reflects its current explanatory strength. Evidence acts as a projection that reshapes these amplitudes rather than immediately collapsing them into a single outcome.

Crucially, hypotheses can interfere with one another. Some explanations reinforce each other through constructive interference, while others weaken each other through destructive interference. This allows the system to capture relationships that classical probability models struggle to represent, such as partial compatibility or contextual dependence.

But this approach also departs from classical logic in another way. Traditional inference requires a strict matching between formulas: the premises must align exactly for a conclusion to follow. Quantum abduction, in contrast, relies on semantic proximity, as measured by modern AI language models that encode meaning as geometric distance. Two statements do not have to be identical to interact; they just need to be close enough in meaning. This flexibility brings formal reasoning closer to practical, real-life use, where approximate relevance often matters more than exact correspondence.

From competition to cooperation in reasoning

One of the most distinctive contributions of quantum abduction is its reframing of explanatory competition. Classical abductive systems enforce a winner-takes-all dynamic. By contrast, quantum abduction allows explanations to both cooperate and compete.

Pareschi introduces the concept of co-opetition, a coordinated exploration in which different hypotheses inform and strengthen one another. Evidence gathered in support of one explanation is evaluated against all others, enabling cross-fertilisation rather than siloed reasoning.

This approach has important organisational implications. In scientific research, it could reduce destructive rivalry between theoretical schools by preserving multiple explanatory trajectories until decisive evidence emerges. In criminal investigations, it could mitigate tunnel vision by keeping alternative narratives active and visible. Rather than treating uncertainty as a problem to be eliminated, quantum abduction treats it as a resource to be managed transparently.

Medical diagnosis and the value of delayed collapse

The paper illustrates the framework using a clinical case involving rapidly progressing paralysis. The medical team faced a diagnostic dilemma between botulism and Guillain-Barré syndrome, two conditions requiring radically different treatments. Early test results were contradictory, making premature commitment risky.

A classical reasoning system would attempt to select the most likely diagnosis based on available evidence. Quantum abduction, by contrast, maintains both hypotheses in superposition. This allows clinicians to pursue parallel, low-regret treatments until further evidence clarifies the situation.

This strategy mirrors actual expert practice. Experienced clinicians often treat multiple conditions simultaneously when the cost of delay is high and the evidence is ambiguous. Quantum abduction provides a formal model of this behaviour, making it explicit and operational rather than intuitive and undocumented.

In this sense, the framework aligns artificial intelligence reasoning more closely with human clinical judgment rather than attempting to replace it.

Crime, literature, and the logic of collective explanation

The framework also sheds light on criminal reasoning, including cases that have resisted definitive resolution for decades. In historical investigations such as the death of King Ludwig II of Bavaria, competing explanations, including suicide, murder, and accidental death, have long been treated as mutually exclusive. Quantum abduction allows these narratives to coexist and interact, producing a more nuanced interpretation of the evidence.

For example, in Agatha Christie’s Murder on the Orient Express, detective Hercule Poirot refuses to eliminate suspects one by one. Instead, he maintains all plausible narratives until the evidence forces a collective explanation. The final solution is not a single culprit but a coordinated act involving all suspects.

Pareschi argues that this narrative structure exemplifies quantum abductive reasoning. What appears to be a literary twist is in fact a precise demonstration of how explanatory superposition can resolve contradictions that classical logic cannot.

A more recent example is the Bossetti-Gambirasio case in Italy, where a controversial conviction rested on nuclear DNA evidence despite contradictory findings from mitochondrial and Y-chromosome analysis. Classical reasoning demanded closure; quantum abduction would instead keep the evidential tensions visible, distinguishing judicial finality from epistemic certainty and preserving alternative hypotheses for future scrutiny.

Reference

Pareschi, R. (2025). Quantum abduction: A new paradigm for reasoning under uncertainty. Sci, 7(4), 182. https://doi.org/10.3390/sci7040182