Across the developing world, migration from rural areas to cities has long been framed as a pathway to economic mobility. Young people leave their villages in search of work, education, and opportunity, often sending money home and easing household poverty. Yet in recent years, a growing number of these migrants have been returning to their rural origins. Economic shocks, health concerns, family obligations, and labour market instability have accelerated this trend, particularly in Southeast Asia.

A new study titled “Return Migration, Crime, and Conflict in Rural Thailand” published in The Journal of Development Studies challenges a common assumption about what happens next. While return migration is often associated with positive economic spillovers, the research shows that its social consequences can be far more complex. Drawing on more than a decade of longitudinal data from rural Thailand, the study finds that returning migrants do not increase general crime, but they are linked to a rise in business-related conflict, particularly business fraud, months after their return.

The research, led by Tri Anh Duc Nguyen of Leibniz University Hannover, offers one of the most detailed empirical examinations to date of how return migration reshapes rural communities. It raises important questions about reintegration policy, rural economic governance, and the fragile balance between opportunity and tension in local economies.

Why return migration rising in rural Thailand

For decades, rural to urban migration has been driven by rapid industrialisation, urban job creation, and widening income gaps between Bangkok and the countryside. Millions of workers from northeastern provinces have spent years employed in construction, manufacturing, and services in cities.

However, return migration has become increasingly common. Structural changes in labour markets, the ageing of migrant workers, and global disruptions such as the COVID pandemic have made long term urban employment less secure. Government initiatives aimed at rural development and local entrepreneurship have also encouraged migrants to return home.

In theory, returnees bring back human capital, financial savings, and social networks that can stimulate local development. Many studies have linked return migration to entrepreneurship, productivity gains, and improved household welfare. Yet these benefits depend heavily on how smoothly returnees reintegrate into local labour markets and social structures.

This is where the Thai case becomes particularly instructive. Rural communities often face limited employment opportunities, high inequality, and strong informal norms governing trust and exchange. When returning migrants re enter these environments, the adjustment process can generate both opportunity and friction.

While return migrants contribute to local economies through acquired social, financial, and human capital, private gains to returnees can generate social costs through business fraud in contexts of weak state capacity and institutional enforcement. Policymakers should balance trade-offs between encouraging economically beneficial return migration and maintaining social cohesion in communities.

Studying crime and conflict beyond simple assumptions

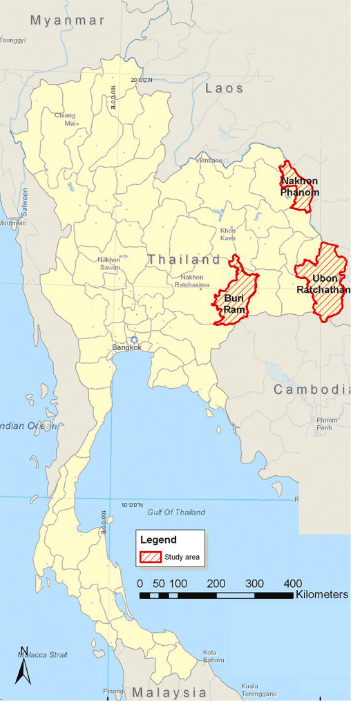

Using panel data from 110 subdistricts across three northeastern provinces between 2010 and 2022, the researchers analyse how changes in the number of return migrants affect local crime and conflict over time. The dataset allows them to track not only immediate effects but also delayed impacts up to nine months after migrants return.

To address the challenge of causality, the study employs advanced econometric techniques, including three stage least squares estimation and an instrumental variable strategy based on unemployment rates in destination provinces. This approach helps isolate the effect of return migration itself, rather than confounding factors such as local economic downturns or pre existing crime trends. Crucially, the analysis differentiates between neighbour conflicts, business fraud, and general crime. This distinction reveals a pattern that would be invisible in more aggregated crime statistics.

What the data reveals about crime

One of the most striking findings of the study is what it does not find. Return migration does not increase property crime or general criminal activity in rural Thailand. In fact, in the immediate months following return, some forms of low impact crime appear to decline slightly.

This challenges widespread fears that returning migrants bring criminal behaviour back from urban areas or that increased population pressure automatically translates into higher crime rates. The evidence suggests that voluntary returnees do not destabilise rural communities through theft, violence, or neighbour disputes.

Furthermore, it indicates that return migration should not be framed as a public safety threat in the conventional sense. Rural crime prevention strategies that focus narrowly on policing or surveillance may therefore miss the real dynamics at play. However, the absence of general crime does not mean the absence of conflict.

The rise of business fraud as a hidden consequence

While overall crime remains stable, the study identifies a consistent and statistically significant increase in business fraud associated with return migration. This effect does not appear immediately. Instead, it intensifies between four and nine months after migrants return to their home subdistricts.

Business fraud in this context refers to deceptive practices affecting local enterprises, such as breach of informal contracts, misrepresentation in transactions, or exploitation of trust based relationships. These incidents are reported by households as economic shocks and are aggregated at the community level.

The findings suggest that a ten percent increase in the return migrant population leads to measurable growth of 0.12-2% in business fraud over time. Importantly, this effect is not mirrored in neighbour conflicts, indicating that the tension is economic rather than purely social. It points to structural pressures in local labour and product markets rather than interpersonal hostility or cultural mismatch alone.

Understanding the economic mechanisms behind conflict

Why would returning migrants be linked to business fraud but not to other forms of crime? The study offers several complementary explanations rooted in economic theory and migration research.

First, selection effects play a role. Return migrants in rural Thailand tend to have lower educational attainment and poorer health than those who remain in urban areas. Many return due to job loss, illness, or unmet expectations. These characteristics can limit their ability to secure stable livelihoods upon return.

Second, labour market competition intensifies. Rural economies often cannot absorb large inflows of working-age adults, particularly when agricultural employment dominates, and non-farm opportunities are scarce. As returnees seek income, competition increases, wages are suppressed, and informal economic activity expands.

Third, skill mismatch becomes a source of frustration. Skills acquired in urban settings may not translate easily into rural enterprises. When aspirations shaped by urban labour markets collide with limited local demand, economic stress rises.

In this environment, business relationships become a site of conflict. Informal credit arrangements, trust-based transactions, and small-scale entrepreneurship are especially vulnerable. The study suggests that some returnees may engage in opportunistic or fraudulent behaviour as a coping strategy, particularly when reintegration support is weak.

The role of time and adjustment

One of the most valuable contributions of the research is its attention to timing. The effects of return migration are not static. Immediate impacts differ markedly from medium-term outcomes.

In the short term, returnees may rely on savings, family support, or a delayed job search. These buffers can temporarily reduce economic pressure. Over time, however, as resources are depleted and expectations remain unmet, tensions surface.

The concentration of business fraud between four and nine months after return reflects this adjustment process. It highlights the importance of viewing return migration not as a single event but as a dynamic transition unfolding over months or even years.

Local communities also respond over time. The study finds evidence that informal governance and social norms eventually adapt, potentially mitigating some of the negative effects. However, this adjustment is uneven and may come at a cost to trust and economic stability.

The authors argue that the negative effects identified in the study are not inevitable. Rather, they reflect gaps in reintegration support and local economic planning.

Reference

Nguyen, T. A. D., & Nguyen, T. T. (2025). Return migration, crime, and conflict in rural Thailand. The Journal of Development Studies. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2025.2563847