Water is a fundamental pillar of the Moroccan economy, while also being one of its most strategically vulnerable resources. In the Souss-Massa basin in southwestern Morocco, persistent depletion of groundwater, rising temperatures, and increasing rainfall variability are converging to create a multidimensional and growing water crisis. For several decades, agricultural intensification and urban development have been supported by intensive groundwater extraction; however, the basin’s hydrological balance is now in a state of pronounced imbalance.

A recent study conducted by Ayoub Guemouria at the International Water Research Institute (IWRI) of Mohammed VI Polytechnic University (UM6P), entitled “Using System Dynamics to Inform Scenario Planning: Application to the Souss-Massa Basin, Morocco“, and published in the Journal of Urban Management, rigorously examined this challenge through the application of the System Dynamics (SD) modelling approach. The main objective was to transcend conventional static water accounting approaches by explicitly simulating the dynamic interactions among social, economic, and environmental subsystems over extended time horizons.

The results indicate that, under a Business-As-Usual (BAU) trajectory, regional groundwater reserves may decline by an average of approximately 337 million cubic meters between 2022 and 2050. Nevertheless, the analysis also identifies viable adaptation pathways. Policy scenarios incorporating improvements in irrigation efficiency, large-scale desalination, and systematic reuse of treated wastewater demonstrate the potential to halt, and possibly reverse, groundwater depletion, thereby steering Morocco toward a more resilient and sustainable water governance framework.

The basin under stress

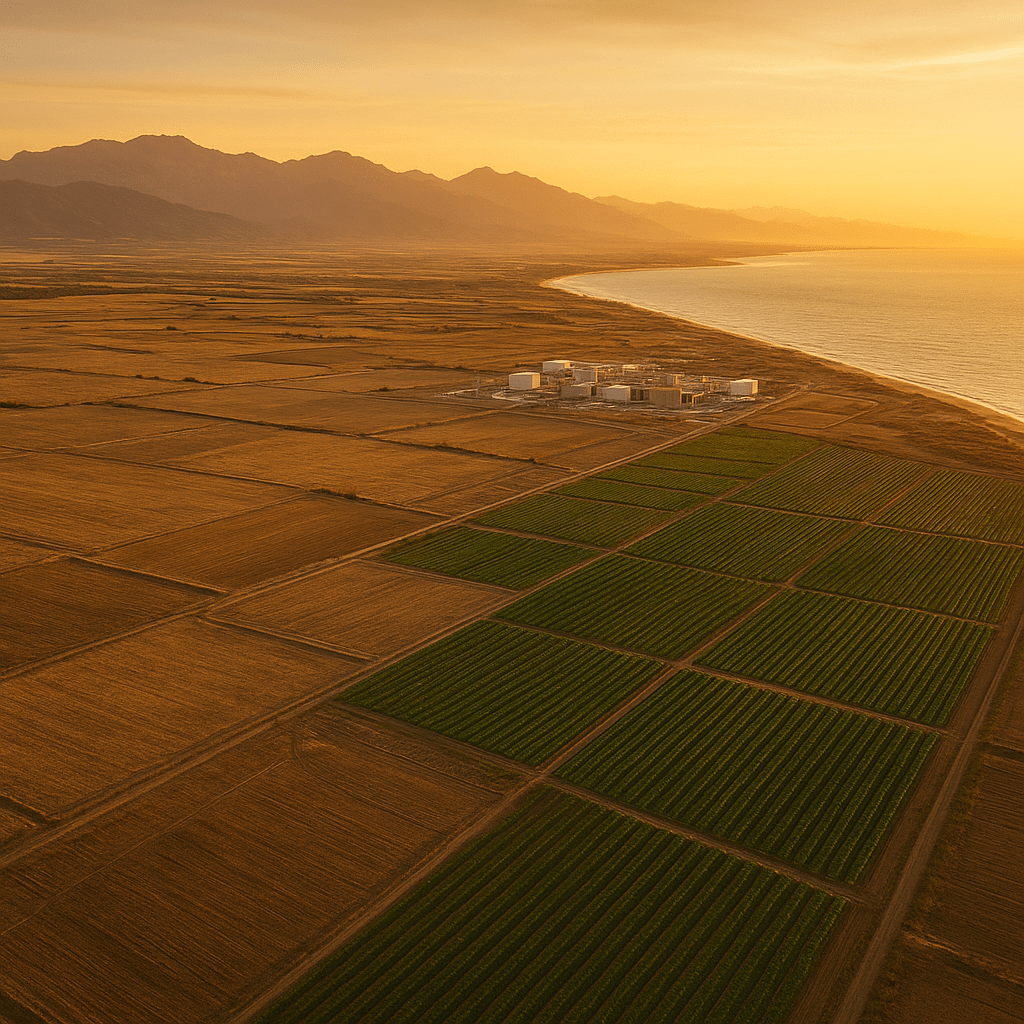

The Souss-Massa region covers approximately 27,000 square kilometers and is bounded by the High Atlas to the north, the Anti-Atlas to the south, and the Atlantic Ocean to the west. This heterogeneity gives rise to pronounced climatic gradients, with mean annual precipitation decreasing from about 600 mm in the northern areas to nearly 150 mm in the southern zones. Beneath this landscape lie the aquifers of Souss, Massa, and Tiznit, which together constitute the main groundwater reserves supplying agricultural production, industrial activities, and the tourism sector.

Agriculture is the dominant water user, accounting for nearly 90% of total withdrawals. The regional economy is strongly dependent on irrigated agriculture, which underpins the production of the majority of Morocco’s exported vegetables and citrus crops. However, this agricultural intensification has generated substantial environmental pressures. According to the Souss-Massa River Basin Agency (ABHSM), annual abstractions exceed renewable water resources, resulting in a severe water deficit.

At the same time, climate change is exacerbating existing pressures on the basin. National projections indicate an average reduction in precipitation of around 15% compared to historical reference periods, accompanied by a decrease in groundwater recharge of up to 27% in some sub-basins. Rising temperatures and longer periods of drought further limit natural recharge processes while increasing evaporation losses from surface reservoirs and soils. Under these conditions, conventional water management paradigms are increasingly unable to ensure the long-term sustainability of the Souss-Massa hydrological system.

Why System Dynamics matters

To address such a complex challenge, a holistic and integrative approach is essential. SD provides precisely this analytical framework. Originating from the seminal work of Jay W. Forrester in the 1950s, SD is a formal modelling methodology that conceptualises complex systems through stocks and flows interconnected by feedback loops. Stocks denote state variables or accumulations, such as groundwater storage, while flows represent dynamic processes including abstraction, recharge, and precipitation.

Unlike static or equilibrium-based models, SD enables the simulation of long-term co-evolution among water resources, energy systems, demographic dynamics, and policy interventions over multi-decadal horizons. The approach explicitly captures both reinforcing (positive) and balancing (negative) feedback mechanisms. For instance, a reinforcing loop may describe how expanded irrigation enhances agricultural productivity, thereby stimulating further water demand, whereas a balancing loop may reflect how increasing water scarcity constrains that demand.

In this study, the SD model systematically linked hydrological and socio-economic subsystems to evaluate water availability, consumption patterns, and management strategies. The SD model integrated heterogeneous data sources, including records from the ABHSM, national statistical databases, and climate projection scenarios, to generate forecasts up to 2050. Key parameters, such as population growth rates, irrigation efficiency, desalination capacity, and wastewater reuse, were explicitly incorporated to explore and compare alternative policy pathways.

This SD modelling framework thus constitutes a conceptual and operational bridge between scientific analysis and real-world decision-making. It enables policymakers to conduct virtual experiments on prospective interventions and to anticipate their long-term systemic impacts prior to implementation.

Data-driven scenario planning

The study developed seven scenarios representing a spectrum of plausible future trajectories for the Souss-Massa basin. The baseline, or BAU scenario, reflects current water management practices extrapolated to 2050. Under this trajectory, water demand persistently exceeds available supply, resulting in pronounced groundwater depletion and a sustainability index (SI) declining below critical threshold levels.

Scenario 1 simulated a 10% improvement in irrigation efficiency, achievable through the expanded adoption of drip irrigation systems and precision agriculture techniques. Scenario 2 increased this target to a 20% efficiency gain, while Scenarios 3 and 4 introduced additional supply-side measures: Scenario 3 incorporated a doubling of recycled water volumes, and Scenario 4 combined this measure with a doubling of desalinated water production.

Scenario 5 proposed a realistic and balanced portfolio of interventions, including moderate improvements in irrigation efficiency, stabilization of the irrigated area, and enhanced contributions from water reuse and desalination. Scenario 6 extended this approach by increasing total water availability by 7% through the development of new infrastructure, such as dams. Finally, Scenario 7 assumed a 15% reduction in irrigated areas, specifically targeting water-intensive crops such as bananas and forage crops, while preserving the gains achieved in irrigation efficiency and non-conventional water resources.

Each scenario was simulated over the 2022-2050 period using an annual time step.

What the model reveals

Under the BAU scenario, the SI declines to near-zero values, reflecting a state of persistent and severe water stress. Cumulative groundwater depletion reaches approximately 337 million cubic meters by 2050, and water supply exceeds demand in only a single year (2027).

A 10% improvement in irrigation efficiency reduces cumulative groundwater drawdown to about 250 million cubic meters, while a 20% efficiency gain further lowers depletion to 163 million cubic meters. Nevertheless, these improvements remain insufficient to ensure system sustainability in the absence of complementary interventions.

The combined implementation of irrigation efficiency improvements, wastewater reuse, and desalination yields the most significant benefits. Scenario 4, which doubles both wastewater reuse and desalination capacities, leads to a slight but positive groundwater recharge of 6.8 million cubic meters. Scenario 6, incorporating additional water supply infrastructure, achieves a recharge of 8.2 million cubic meters. Scenario 7, based on a reduction in irrigated area, results in a modest yet positive recharge of 1.6 million cubic meters, while preserving overall agricultural productivity.

Overall, the results demonstrate that integrated water resources management, rather than isolated sectoral measures, is essential for reversing the current unsustainable trajectory. Scenarios 4, 6, and 7 emerge as the most robust long-term strategies for ensuring the sustainability of water availability.

Lessons for decision-makers

The study highlights the urgent need to integrate systemic modelling into national water planning. The Souss-Massa basin is a representative case study of Morocco’s National Water Program (2020-2050) and Green Generation Strategy (2020-2030), both of which aim to reconcile economic development objectives with long-term sustainability imperatives.

SD provides a robust analytical framework for the quantitative exploration of such public policies. By explicitly representing the co-evolution of water demand, water supply, and policy interventions over time, SD enables decision-makers to rigorously assess trade-offs among infrastructure investments, agricultural productivity, and environmental conservation objectives.

However, the study also brings to light several structural limitations. Reliable datasets remain limited, particularly with respect to groundwater dynamics, industrial water use, and long-term trends in irrigation efficiency. Socio-economic information is fragmented across multiple institutions, while numerous hydrological monitoring stations lack continuous and high-resolution data acquisition. These deficiencies constrain the reliability of model projections and emphasize the critical need for strengthened coordination between research bodies and governmental agencies.

Despite these constraints, the SD model developed for the Souss-Massa basin demonstrates a high degree of adaptability and replicability. With appropriate local calibration and data integration, it can be extended to other river basins in Morocco, as well as to comparable arid and semi-arid regions across North Africa and the Middle East.

From models to reality

The transition from modelling to implementation requires both sustained political commitment and substantial financial investment. Desalination infrastructures, wastewater treatment systems, and irrigation modernisation programmes require significant upfront capital expenditures (CAPEX), as well as long-term operational and maintenance resources (OPEX).

The social dimension of implementation is equally crucial. Farmers and local communities must be actively engaged as key stakeholders in the planning, decision-making, and adoption of water-saving practices. Measures such as the reduction of irrigated areas or shifts in crop patterns may have direct implications for livelihoods; therefore, the establishment of appropriate compensation schemes and incentive mechanisms is essential to ensure social acceptability and economic resilience.

Participatory approaches, notably shared-vision modelling, provide an effective means of addressing this implementation gap. By integrating stakeholders throughout the modelling process, policymakers can foster trust, improve collective understanding of SD, and enhance the alignment of proposed interventions with local priorities and constraints. Such participatory SD approaches have demonstrated their effectiveness in other regions confronted with comparable water scarcity and sustainability challenges.

Bridging science and sustainability

The strength of the SD approach lies in its capacity to coherently integrate the physical and human dimensions of water resource management. By coupling hydrological modelling with socio-economic analysis, it enables the explicit representation of feedback mechanisms that are frequently overlooked by conventional, reductionist approaches. For example, it captures how the growth of tourism intensifies domestic water demand, or how improvements in irrigation efficiency can simultaneously mitigate groundwater depletion while sustaining agricultural economic output.

Moreover, SD supports robust, scenario-based planning under conditions of climatic uncertainty. Rather than relying on deterministic forecasts, it explores the dynamic behaviour of the system across alternative climate trajectories, policy interventions, and behavioural responses. This confers particular relevance to SD as a decision-support tool for climate adaptation in water-scarce regions.

The SD model adopted the optimistic climate pathway. Nevertheless, even under these conditions, the long-term sustainability of the basin’s water resources remains precarious. The implication is unequivocal: in the absence of coordinated and integrated management actions, the combined pressures of climate change and resource overexploitation are likely to drive the system beyond its resilience threshold.

Conclusion and perspectives

The conceptual transition from hazard-centered approaches to vulnerability-oriented frameworks requires a redefinition of analytical priorities. First, emphasis must be placed on the territorial scale, understood as a subnational locus where societal, ecological, institutional, political, and economic dynamics intersect, and within which public action is operationalized. Second, the diversity of actors involved in territorial governance, across urban, peri-urban, and rural contexts, critically conditions the effectiveness of mitigation, adaptation, prevention, and anticipatory strategies.

Territories must retain the capacity to define endogenous development trajectories that foster social cohesion while reducing climate-related vulnerabilities. Local stakeholders should be safeguarded against the imposition of standardized technical prescriptions that are misaligned with territorial specificities, financial constraints, or innovation capacities. A fundamental prerequisite for sustainability lies in dismantling cognitive and policy silos. When multi-actor synergies mature through inclusive, balanced, and consensual governance processes, they generate positive externalities for regional governance, particularly in enhancing climate adaptation. Conversely, deficient governance, or systemic inaction, produces substantial socio-economic and environmental costs, both visible and latent, at the regional scale.

Looking ahead, the integration of SD with emerging technologies opens new methodological frontiers. Coupling SD with machine learning algorithms and real-time monitoring systems can improve predictive performance and enable adaptive management. Smart sensors and satellite-based observations can continuously feed SD models, providing decision-makers with near-real-time situational awareness.

Water security thus emerges not merely as a technical issue, but as a fundamentally societal challenge. The Souss-Massa basin exemplifies both the consequences of unsustainable resource exploitation and the transformative potential of science-based policy design. A systemic understanding of water resources enables Morocco to formulate coherent policies that safeguard water availability, sustain agricultural systems, and enhance resilience under climate uncertainty.

Future research and policy efforts should therefore focus on strengthening monitoring infrastructures through the integration of remote sensing and real-time climate data to enhance SD model robustness; coupling SD models with multi-criteria decision-support tools to assess trade-offs; conducting comprehensive economic analyses (CAPEX/OPEX) to evaluate scenario costs (MDH) and quantify water gains and losses (Mm³/year); optimizing scenarios through error-propagation analysis and mathematical optimization; and ensuring socio-economic feasibility and social acceptability via inclusive multi-stakeholder governance platforms. From data to decisions, the convergence of SD, artificial intelligence, remote sensing/GIS offers a powerful framework for capturing basin-scale variability and advancing sustainable water governance in Morocco.

Reference

Guemouria, A., Chehbouni, A., Belaqziz, S., Dhiba, D., & Bouchaou, L. (2025). Using system dynamics to inform scenario planning: Application to the Souss-Massa basin, Morocco. Journal of Urban Management, 14, 753–768. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jum.2025.01.012