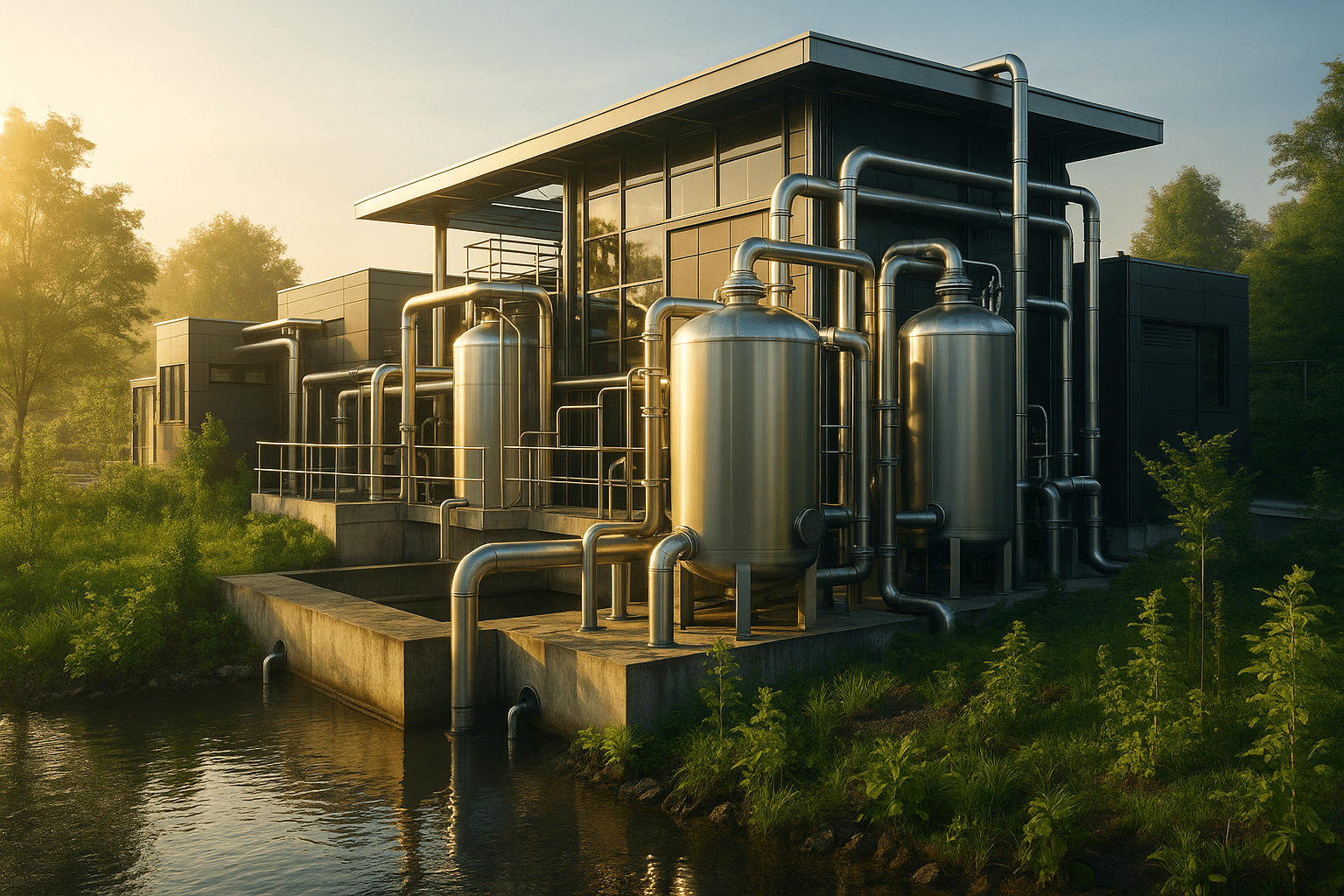

Every day, billions of litres of wastewater course through our treatment plants, carrying away not just human and industrial waste but also one of agriculture’s most vital ingredients: phosphorus. Often dismissed as mere waste, sewage sludge is a hidden reservoir of this non-renewable nutrient. But what if this smelly by-product could become a sustainable source of clean phosphorus fertiliser? A new study from researchers at Nanyang Technological University (NTU), Singapore, suggests it can, with the right chemistry.

Published in the journal Resources, Conservation & Recycling, the study led by Satya Brat Tiwari proposes a cleaner and more efficient method of phosphorus recovery that could significantly reduce our dependence on phosphate rock, a dwindling natural resource. As the world grapples with both resource scarcity and rising environmental pressures, this breakthrough offers a timely and potentially game-changing solution.

A question of waste or resource?

Phosphorus is essential for food production. It helps plants grow, and without it, modern agriculture would collapse. Yet global phosphorus reserves are finite. Nearly 90% of the mined phosphate rock is used in fertilisers, and supply chains are concentrated in just a handful of countries. As geopolitical tensions grow and extraction becomes more expensive and polluting, scientists are increasingly looking toward alternative sources.

Sewage sludge, the semi-solid by-product from wastewater treatment plants, is one such alternative. Rich in phosphorus, it also contains a host of harmful trace elements like heavy metals. Extracting usable phosphorus without these contaminants has been a scientific challenge until now.

What the researchers did differently

Traditionally, sewage sludge has been incinerated to recover phosphorus from the resulting ash. But this approach is both energy-intensive and environmentally taxing. It requires drying the sludge and contributes significantly to greenhouse gas emissions. Moreover, the process doesn’t effectively deal with the co-extraction of toxic trace elements.

Tiwari and his colleagues tried a different route: hydrothermal carbonisation (HTC), which allows for the treatment of wet sludge without the need for drying. The team took a unique two-step approach. First, they mixed sewage sludge with alum sludge, a by-product from drinking water treatment rich in aluminium. They then subjected this mixture to acidic HTC. This step helped transform phosphorus compounds into a more alkaline extractable form. Second, they performed alkaline extraction, which enabled the clean separation of phosphorus while leaving harmful trace elements behind.

Why this method matters

The method was effective. Under optimised conditions, specifically a temperature of 240 degrees Celsius, an acidic feedstock pH of around 3 to 4, and an aluminium-to-phosphorus molar ratio of 4, the researchers achieved up to 82% phosphorus recovery. This was more than double the recovery rate of traditional methods. Overall, their recovery process ranged from 59% to 75%, compared to 30% to 37% in reference scenarios.

Crucially, this method also limited the co-extraction of toxic trace elements like zinc, nickel, and chromium. These metals were largely immobilised in the solid hydrochar, reducing the environmental risks associated with using recovered phosphorus in agriculture.

The chemistry behind the recovery

Understanding why this method works requires a brief dive into phosphorus chemistry. In sewage sludge, phosphorus exists in several forms. Calcium phosphate (Ca-P) is one of the most common phosphorus species in sludge but is not easily extractable. The acidic HTC treatment promotes the transformation of Ca-P into aluminium phosphate (Al-P), which dissolves more readily in alkaline conditions.

By using alum sludge, already rich in aluminium ions, the team harnessed a cost-effective source of Al to drive this chemical transformation. The subsequent alkaline extraction then allowed Al-P to be selectively dissolved, leaving behind most other undesirable elements. Sophisticated analysis techniques, including solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), confirmed these molecular-level transformations.

Hydrothermal treatment is not new, but its full potential is yet to be unravelled

– Satya Brat Tiwari

A tale of two wastes

What makes this study even more compelling is its circularity. Not only does it recover phosphorus from sewage sludge, but it also finds a use for alum sludge, which is typically discarded in landfills. Both types of sludge are common waste products in urban infrastructure, yet both hold untapped potential.

Singapore, where the study was conducted, exemplifies the challenge and opportunity. With its limited land and high population density, the city-state faces significant pressure to manage waste sustainably while ensuring food security. This method could be a model for other densely populated urban areas looking to close the nutrient loop.

Environmental and economic implications

The environmental benefits of this method are clear. By bypassing incineration, the HTC-based approach slashes carbon emissions. It also reduces the leaching risk of heavy metals into soil and water when phosphorus is reapplied as fertiliser. But what about the economics?

Here, too, the outlook is promising but complex. While the process uses common reagents like hydrochloric acid and sodium hydroxide, the latter is a significant cost factor. For each kilogram of phosphorus recovered, around 64 kg of NaOH is required. Yet researchers suggest that this cost can be offset by integrating the process with facilities that can supply or recycle these reagents, such as those treating brine using electrosynthesis.

Further, the by-products of the process, hydrochar, aluminium hydroxide, and clean phosphorus salts, all have commercial value. Hydrochar can be used as a soil amendment or fuel; aluminium hydroxide can serve as a coagulant in water treatment; and phosphorus can be sold as fertiliser. These revenue streams could make the process not just sustainable, but profitable.

Rethinking what we flush away

This study prompts a broader societal question: What if waste isn’t waste at all? As cities grow and resources become scarcer, the lines between what we discard and what we can reuse are blurring. Tiwari and his team show that with the right science, even sewage sludge can become a valuable resource.

Governments, industries, and policymakers must now take up the baton. Investments in pilot plants, public-private partnerships, and policies supporting resource recovery are needed to take this science from the lab to the landscape.

If we fail to act, the costs could be severe. But if we succeed, we could turn one of our dirtiest problems into a clean solution. The future of fertilisers may well lie in the flush.

References

Tiwari, S. B., Veksha, A., Chan, W. P., Fei, X., Liu, W., Lisak, G., & Lim, T. T. (2025). Acidic hydrothermal carbonization of sewage sludge for enhanced alkaline extraction of phosphorus and reduced co-extraction of trace elements. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 212, 107936. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2024.107936