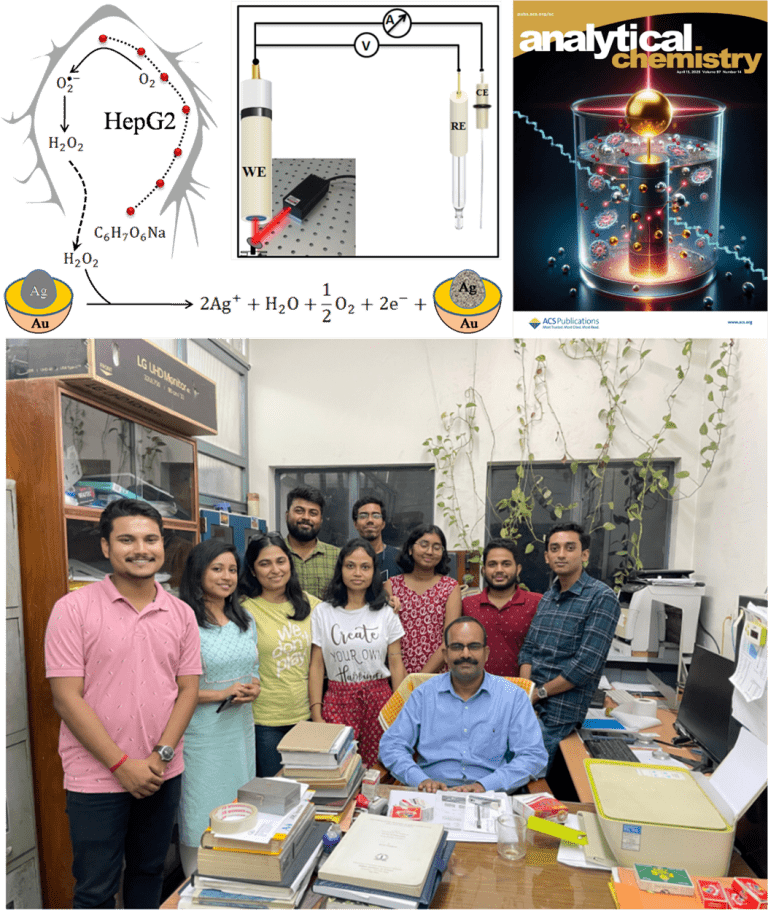

Researchers (M. Ghosal et al.) from the Saha Institute of Nuclear Physics in India have developed a gold-coated silver nanocatalyst that can detect trace amounts of hydrogen peroxide released by cancer cells. The work, led by Dulal Senapati, has been published in Analytical Chemistry under the title Core to shell thickness regulated Ag@Aunanocatalyst for LSPR improved in situ detection of extracellular peroxide: Response in a cancer cell.

Hydrogen peroxide is more than a common disinfectant. Inside the body, it acts as a significant signaling molecule that guides the behavior of cancer cells. Measuring its release is increasingly recognised as a potential method for tracking cancer progression and understanding how tumour cells respond to metabolic stress. However, detecting these molecular traces in real-time has remained technically challenging.

The team’s new core to shell nanocatalyst changes this landscape. The researchers created a silver core enclosed within a gold shell, which behaves as a highly efficient plasmonic sensor capable of amplifying electrochemical signals. When illuminated, the nanocatalyst generates energetic charge carriers that accelerate the reduction of hydrogen peroxide. This allows the system to detect concentrations far lower than those accessible to many conventional sensors.

Why hydrogen peroxide matters in cancer biology

Hydrogen peroxide may appear to be a simple molecule, but inside living cells, it acts as a reactive oxygen species and an important secondary messenger. Cancer cells release it during metabolic activity and particularly under stress conditions. Its presence helps regulate cell proliferation, migration, and programmed cell death.

Because hydrogen peroxide levels rise during cancer progression, monitoring this biomarker is a promising way to follow tumour activity. Detecting small variations in peroxide release can provide insight into oxidative stress responses and may one day support early diagnosis or the monitoring of treatment.

However, peroxide levels in physiological environments are extremely low, typically in the micromolar range. Measuring these concentrations requires sensors that are both exceptionally sensitive and highly selective. Many existing approaches rely on surface-enhanced Raman scattering or enzyme-based assays. Although useful, they often struggle with linearity, reproducibility or interference from other biomolecules.

The new study addresses these limitations by harnessing localised surface plasmon resonance, an optical effect that occurs in noble metal nanoparticles and that can be used to amplify electrochemical reactions.

How the gold-coatednanocatalysts were engineered

The research team synthesised three versions of their core-to-shell nanoparticle system, referred to as CSNP1, CSNP2, and CSNP3. Each consisted of a silver core surrounded by a controllable gold shell thickness. This design is scientifically significant because silver has strong plasmonic properties but limited stability in biological conditions. Gold is more stable but produces a different optical response. Combining the two metals enables researchers to leverage the strengths of both.

Producing a reliable gold-coated silver nanostructure is not straightforward. Gold tends to displace silver ions during synthesis, which can destabilise the structure. To overcome this, the team used a carefully optimisedseed-mediated growth method that allowed the gold shell to form gradually while retaining the silver core.

Advanced characterisation techniques confirmed the success of the synthesis. Transmission electron microscopy revealed distinct core and shell boundaries. X ray diffraction showed that the particles crystallised in face centred cubic arrangements. X ray photoelectron spectroscopy verified the oxidation states of the metals, with the surface gold remaining metallic and the silver core retaining its elemental form in most samples.

Among the three nanoparticles tested, CSNP2 displayed the most favourable balance between core size and shell thickness. It also exhibited the highest microstrain, which is associated with increased catalytic activity. This sample became the primary candidate for biological sensing experiments.

Why plasmonics improves sensing performance

Localised surface plasmon resonance occurs when the conduction electrons at the surface of metal nanoparticles oscillate collectively in response to incident light. This produces an intense electromagnetic field around the particle. When exploited correctly, this effect can generate energetic charge carriers known as hot electrons and hot holes.

In the context of hydrogen peroxide sensing, these hot electrons accelerate the electrochemical reduction of peroxide at the nanoparticle surface. As a result, the sensor produces a stronger and more easily measurable current. This process, known as plasmon-enhanced electrocatalysis, enables the detection of hydrogen peroxide at significantly lower concentrations than traditional electrochemical sensors.

The gold shell absorbs the incident light and generates the hot electrons. The silver core contributes by providing additional electrons through a controlled oxidation process. This interplay between the two metals makes the nanocatalyst behave like a tiny internal power source. The reaction continues as long as peroxide is present and the silver core has not been completely oxidised.

This mechanism also provides researchers with deep control over the sensitivity and detection range. By adjusting the shell thickness and illumination intensity, they can fine-tune the catalytic behaviour and optimise the sensor for trace-level detection.

Comparing optical and electrochemical sensing approaches

The researchers first tested the nanoparticles as surface enhanced Raman scattering substrates. They used the Raman active molecule 4 mercapto pyridine (HS-C6H4N) to evaluate the enhancement effect produced by each nanoparticle type. While CSNP3 showed the highest Raman intensity, the response to hydrogen peroxide concentration was not linear enough for reliable quantitative detection.

The electrochemical method, by contrast, offered clear advantages. When the nanoparticles were illuminated at a wavelength of 671 nanometres, the current produced during peroxide reduction increased by a factor of about two compared with the dark condition. This demonstrated strong plasmon-enhanced electrocatalytic activity.

Amperometric measurements at a fixed voltage produced a stable and reproducible signal that increased in proportion to the added peroxide concentration. The sensor achieved a detection limit of 340 nanomolar under optical excitation, positioning it among the more sensitive hydrogen peroxide sensors reported.

The researchers also tested the influence of common interfering molecules such as glucose, urea, dopamine and amino acids. These substances produced negligible changes in current, indicating that the nanocatalyst provided high selectivity. This is essential for cancer-related applications where cell culture media contain many potentially interfering compounds.

Tracking hydrogen peroxide released by cancer cells

To demonstrate real biological relevance, the team applied the sensor to HepG2 liver cancer cells. This cell line is known to release hydrogen peroxide in response tometabolic stress, particularly when exposed to pharmacological concentrations of ascorbic acid. This stress response has been studied for its potential anticancer effects because high-dose ascorbic acid can selectively kill tumour cells.

The researchers placed living HepG2 cells inside an electrochemical chamber and recorded the current before and after the addition of ascorbic acid. When the cells began producing peroxide, the plasmon-enhancednanocatalyst generated a measurable current increase. By comparing this rise in current with the calibration curve, the team calculated that the cells released around 33 micromolar peroxide under the experimental conditions.

The group extended the experiments to two additional cancer cell lines, MCF7 and HeLa. Although these cells behaved differently under stress, the sensor successfully detected peroxide in each case once appropriate conditions were established. These results reinforce the robustness of the sensing platform.

LSPR-coupled electrochemical sensing of trace-level secondary cancer messenger by Ag@Au nanocatalysts.

-Dulal Senapati

The future of plasmon enhanced sensing

The work demonstrates that a carefully designed nanocatalyst can overcome many of the limitations of current peroxide sensing technologies. The results demonstrate that plasmon-driven electrochemistry is not only a laboratory curiosity but a powerful tool for biological detection.

The next steps may include integrating the nanocatalyst into flexible electrodes, microfluidic chips or portable diagnostic devices. Additional research could also explore long-term stability, scaling methods, and applications in clinical contexts.

The study makes a significant contribution to the growing field of plasmon-enhanced analytics, underscoring how engineered nanoscale materials can reveal molecular processes that were previously difficult to measure.

Reference

Ghosal, M., Mondal, S., Ghosh, T., Prusty, D., & Senapati, D. (2025). Core to shell thickness regulated Ag@Aunanocatalyst for LSPR improved in situ detection of extracellular peroxide: Response in a cancer cell. Analytical Chemistry, 97(14), 7651–7661. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.analchem.4c04651

Coauthor

Dr.Manorama Ghosal holds a Ph.D. (2019–2025) in Biophysical Science from the Saha Institute of Nuclear Physics, HBNI. Her work integrates chemical biology with nanotechnology, focusing on the design of plasmonic nano-devices for ultrasensitive chemical detection. She has specialized expertise in Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS), Electrochemistry, and Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM), which she uses to probe nano–bio interactions, characterize molecular architectures and develop advanced sensing platforms. Her research contributions span plasmon-based theranostics, nanoscale mechanochemical analysis, and innovative spectroscopic approaches.