Artificial Intelligence (AI) is no longer a distant promise during modern warfare. From decision support systems that analyse battlefield data to autonomous platforms capable of identifying and engaging targets without human oversight, AI has already begun to shape how wars are planned and fought. Yet one critical question remains underexplored—do the future leaders of the U.S. military trust AI to play such a decisive role in conflict?

This question sits at the heart of a new peer-reviewed study by Paul Lushenko and Robert Sparrow published in Armed Forces and Society and entitled “Artificial intelligence and U.S. military cadets’ attitudes about future war”. Paul Lushenko, who was then affiliated with the United States Army War College, administered a novel survey experiment to expose Cadets to fictional but realistic uses of AI-enabled capabilities that vary in terms of the decision-making level and degree of human oversight. The research offers rare empirical insights into how the next generation of U.S. military officers perceive AI-enabled warfare and whether they are willing to rely on it.

At a time when defence modernization strategies assume enthusiastic adoption of AI by younger personnel, the findings challenge a widely held belief shared by policymakers, military officials, and security analysts. Rather than embracing AI uncritically, U.S. military Cadets appear to hold nuanced and often cautious views about where and how AI should be used in war.

Why Cadets’ views on AI-enabled warfare matter

While the development of novel technologies is necessary for military innovation, it is insufficient. Despite the emergence of new capabilities, militaries can fail to effectively integrate them into their arsenals, especially because of poor user trust. Though senior commanders approve budgets and doctrine governing the use of force, it is junior officers who test, deploy and operationalise new systems. If they lack confidence in AI-enhanced military technologies, the promised advantages of speed, efficiency, and decision superiority during future war may never materialise.

Cadets enrolled in Reserve Officers’ Training Corps programmes across the United States are tomorrow’s platoon leaders, staff officers, and strategic planners. Their beliefs offer a leading indicator of how AI will be integrated into real-world military practice. Understanding Cadets’ trust, or expectations of systems’ performance, is therefore essential for shaping policy, education, and future force design.

The study also speaks to a broader societal concern. Public debates about AI often assume that younger generations are digital natives who instinctively trust data-driven algorithms, such as those used for social media applications. This research suggests that such assumptions may be misplaced, at least in high-stakes domains involving the use of lethal force.

Rethinking how AI is used in war

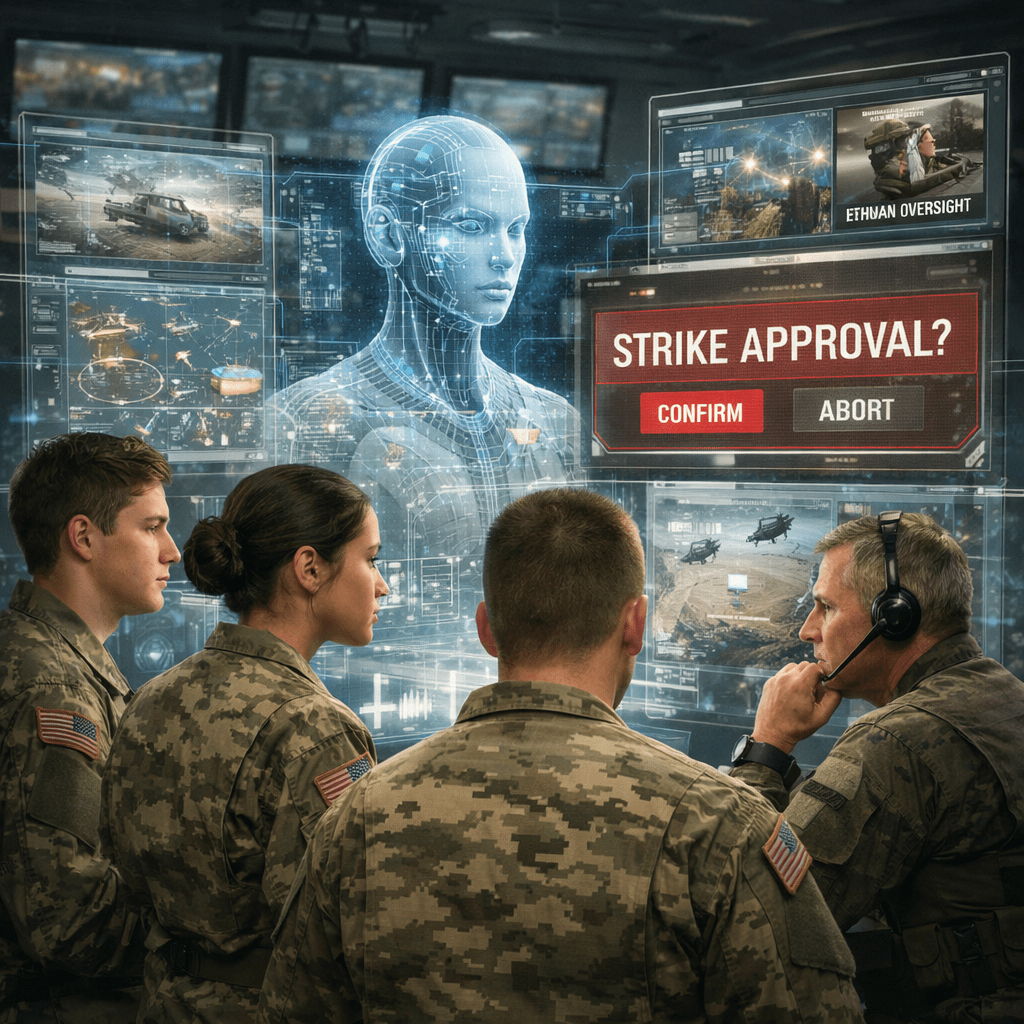

One of the most valuable contributions of the study lies in its categorization of different models of AI-enabled warfare. Rather than treating AI as a single concept, the research conceptualizes AI-enabled warfare along two dimensions. The first is the level of decision-making delegated to AI, whether on the battlefield (tactical) or in the war-room (strategic). The second is the degree of human oversight, ranging from active supervision (“human-on-the-loop”) to near complete autonomy (“human-off-the-loop”).

From these dimensions, four distinct models of AI-enabled warfare emerge. Tactical decision-making with human oversight is described as centaur warfare, where humans and machines operate collaboratively. Tactical decision-making with little human oversight is labelled minotaur warfare, in which machines direct human action. Strategic decision-making without human oversight, sometimes referred to as an “AI general” or “singleton” warfare, represents the most extreme form of AI-enabled warfare. Finally, mosaic warfare combines strategic-level AI decision support with appropriate human oversight, that is, judgment.

No evidence of a trust paradox

Previous research on senior U.S. military officers’ uptake of AI has identified a trust paradox. In some cases, these more experienced officers support the deployment of AI systems even when they do not fully trust them. Lushenko’s study did not identify a similar paradox among U.S. military Cadets. Rather, Cadets’ levels of trust and support for AI-enabled warfare were closely aligned.

This alignment suggests that Cadets may approach AI more dispassionately than their senior counterparts. Instead of deferring to institutional narratives about technological inevitability, as their superiors appear to do, Cadets seem to evaluate AI based on perceived risks, ethical considerations, and operational logic.

Cadets’ perspectives may reflect ongoing cognitive development, limited exposure to military hierarchy, and a greater willingness to question assumptions during training.

What shapes Cadets’ trust in AI

The study also examined why Cadets trust or distrust AI-enabled warfare. Several instrumental, normative, and operational factors emerged as significant.

Instrumentally, fear of strategic disadvantage played a major role. Cadets were more likely to trust AI-enabled warfare if they believed that failing to adopt the practice would leave the United States vulnerable relative to adversaries. This reflects awareness of emerging global competition over military AI capabilities.

Normatively, moral reasoning mattered as well. Cadets were torn between seeing AI as a tool that could reduce risk to soldiers and fearing its potential misuse, similar to critics’ claim of a moral hazard that characterizes U.S. drone strikes. Beliefs about compliance with domestic and international law increased trust, while concerns about abuse of power reduced it.

Operational experience also shaped Cadets’ attitudes of trust. Cadets with prior military service or combat exposure were significantly more trusting of AI-enabled warfare. This suggests that familiarity with the realities of warfare may alter perceptions of automation and risk.

Challenging the myth of the digital native

One of the most striking implications of the research is its challenge to the idea of the digital native. Despite growing up with advanced technology, Cadets were far from uniformly enthusiastic about the use of AI during war. Trust varied widely across individuals and contexts.

Age, education, and experience all influenced Cadets’ attitudes of trust. Most Cadets surveyed were under 25 years of age and had not yet completed a bachelor’s degree. Their responses reflect ongoing cognitive development and professional socialisation rather than blind technological optimism.

In this sense, Cadets may be better described as digital apprentices rather than digital natives. They are learning to engage with AI critically, especially when its use carries ethical and strategic consequences.

–Paul Lushenko

A signal for society beyond the military

Although the study focused on U.S. military Cadets’ trust in AI-enabled warfare, its findings are relevant beyond defence. Questions about trust, oversight, and responsibility for AI are equally applicable to civilian domains, such as healthcare, industry, and policing.

The research suggests that younger generations are capable of nuanced engagement with AI, especially when its consequences are clearly articulated. Trust is not automatic. It is conditional, context-dependent, and shaped by a complex set of underlying values and beliefs.

Reference

Lushenko, P., & Sparrow, R. (2024). Artificial intelligence and U.S. military cadets’ attitudes about future war. Armed Forces and Society, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/0095327X241284264