The concept of ‘Peak Oil’ once captured global anxiety, warning us that a critical resource was running out. Now, a similar, even more alarming metaphor is gaining ground: ‘Peak Soil.’ It suggests that we are nearing the point where the world’s soil productivity will irreversibly crash, jeopardising our ability to grow food and stabilise the climate.

It’s a powerful and persuasive image. However, a new study at the University of Sydney (published in International Soil and Water Conservation Research) argues that while the warning is essential, the metaphor itself is scientifically flawed. Treating soil merely as a finite resource like oil obscures its unique ability to regenerate. It also fails to give policymakers the precise tools they need to halt the decline.

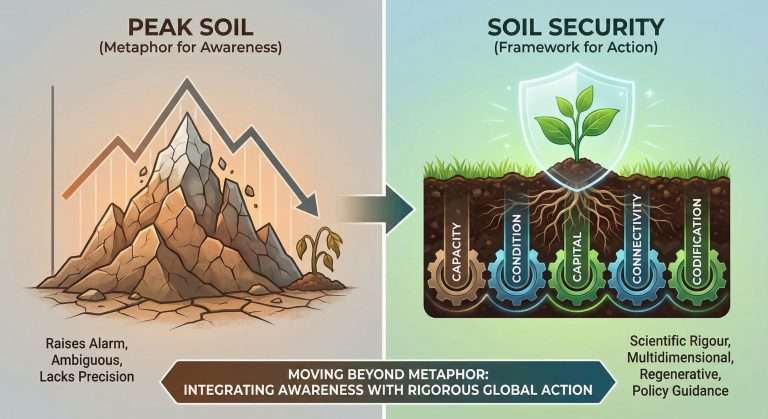

To secure our future, we must move past the dramatic simplicity of ‘Peak Soil.’ We must adopt a more comprehensive approach: the concept of soil security.

More than dirt: The unseen crisis

Soil is not just inert ‘dirt’; it is a living, dynamic system essential to the health of our planet. It stores carbon, filters our water, maintains biodiversity, and underpins roughly 95 per cent of all global food production.

The crisis is staggering. Soil formation is a painfully slow process; it can take over a thousand years to generate just one millimeter of topsoil. Yet, we are destroying it at a destructive speed through intensive farming, deforestation, and climate change. Over the last four decades, up to 40 per cent of the planet’s arable land has been lost to erosion.

This isn’t just a problem for farmers. The economic cost of this degradation is estimated to reach 10% of global GDP annually. Soil loss threatens water quality and drives social instability, meaning the consequences are felt in every supermarket and every government office.

The problem with the 'Peak Oil' analogy

While ‘Peak Soil’ effectively raises public alarm, it breaks down when applied to the complex reality of land management:

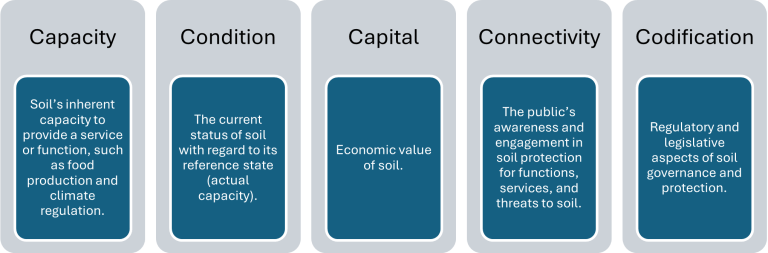

- It isn’t finite: Unlike non-renewable oil, soil is a living system with an incredible capacity to regenerate. Sustainable methods, such as conservation agriculture and agroecology, can help repair degraded land. Framing soil as purely finite risks fosters fatalism rather than motivating restoration.

- Health is complex: Oil reserves are simply measured by volume. Soil health, however, is multidimensional, based on complex physical, chemical, and biological indicators. This makes it impossible to define or detect a single, universal ‘peak’ with scientific rigour.

- The world varies: Soil is highly variable in resilience and composition. A single, global ‘peak’ is irrelevant when soil conditions vary so dramatically. We need locally adapted metrics, not a uniform global threshold.

The real danger, as demonstrated by historical events such as the 1930s US Dust Bowl, is reaching a functional threshold where degradation outpaces the soil’s ability to recover.

The invisibility of soil in policy

One of the greatest hurdles to action is that soil degradation remains largely invisible to our economic and political systems.

Economically, soil is often treated as an expendable input, rather than the natural capital asset it truly is. This asset is globally valued at hundreds of trillions of dollars. By neglecting its economic value, we incentivise short-term exploitation that leads directly to collapse.

Politically, soil governance is fragmented across multiple government portfolios, including agriculture, environment, and land use. Unlike air and water pollution, soil lacks strong, integrated legal frameworks and the enforcement needed to drive global protection. Soil needs robust codification to ensure it is managed as a strategic national and global risk.

Peak Soil’ is the alarm bell; ‘Soil Security’ is the repair manual. One grabs attention, but the other provides the science needed to fix the problem.

-Amin Sharififar

The soil security path to action

To translate the compelling warning of ‘Peak Soil’ into effective policy, we must adopt the Soil Security framework. This approach provides the scientific rigour and multidimensionality that the simple metaphor lacks.

The framework integrates five critical dimensions to assess soil performance and resilience. It moves policy from emotional alarm to scientifically grounded action (Figure 2):

Conclusions

To create impactful change, we need to use the communicative power of ‘Peak Soil’ while applying the scientific precision of the security framework:

- Establish regional thresholds: Stop chasing one global peak. Instead, set regionally adapted metrics, such as measuring the rate of organic carbon decline or erosion that exceeds natural formation levels. This gives local managers actionable data.

- Champion regeneration: Actively incorporate the soil’s capacity to heal. We must promote and invest in proven practices, such as regenerative agriculture, to counteract fatalism and highlight the success stories of landscape rehabilitation.

- Mandate codification: Policy must translate the scientific warning into enforceable action. Governments must establish stronger, unified legal frameworks and ensure sustained investment to safeguard this vital resource.

The urgency of the soil crisis is undeniable. Securing our soil requires rigorous science, innovative governance, and a global commitment to preserve and restore this irreplaceable asset for future generations.

Reference

McBratney, A., Minasny, B., Sharififar, A., Borrelli, P., Evangelista, S. J., Feeth, J., … & Yang, J. E. (2025). Peak Soil: Is It a Useful Concept?. International Soil and Water Conservation Research. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iswcr.2025.11.005