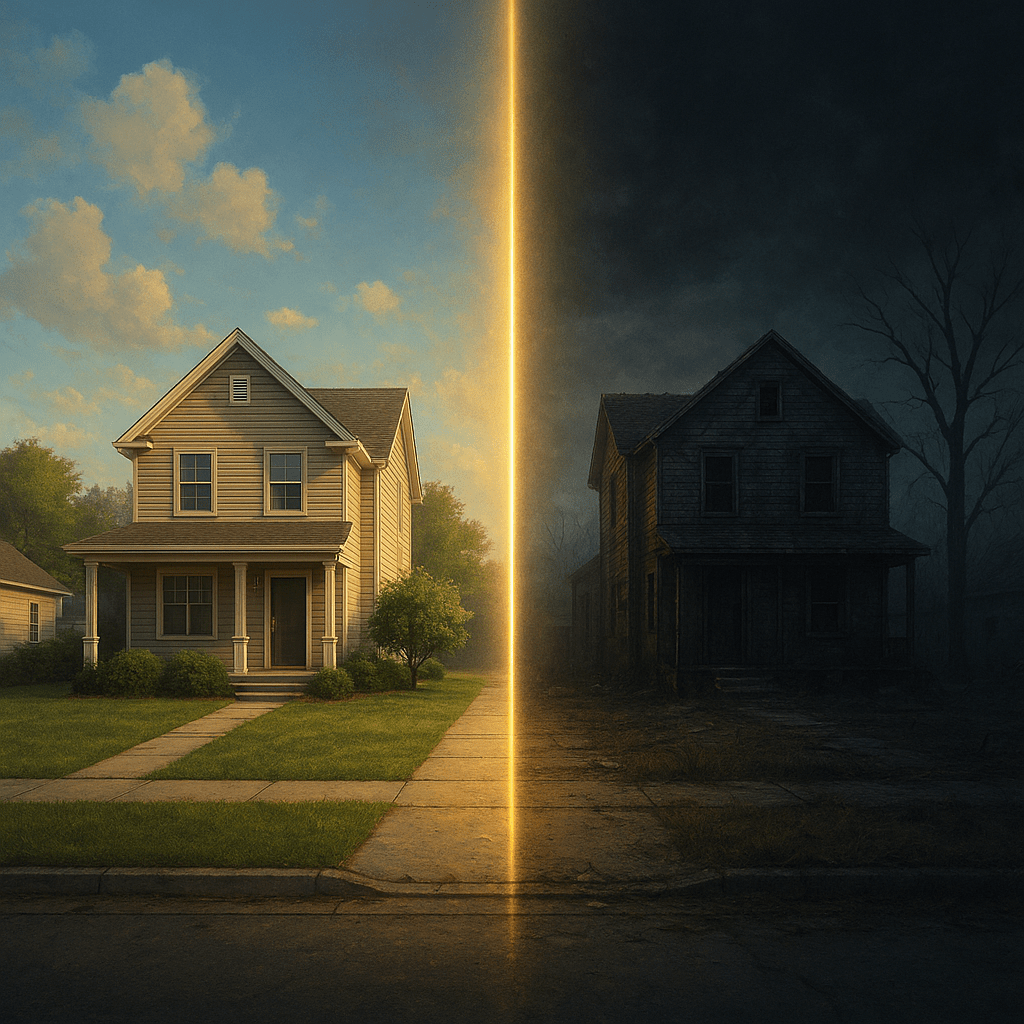

Across the United States, where people live and who their neighbours are may determine how long they live. A new study published in the Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities reveals that racial and economic segregation is not just a social issue but a matter of life and death.

The research, led by Rui Gong from Mercer University, provides one of the most comprehensive analyses to date on how residential segregation affects mortality across more than 3,000 US counties. The findings show that counties with the highest levels of racial and economic segregation have dramatically higher death rates from nearly every major cause of death, including heart disease, cancer, Alzheimer’s disease, diabetes, and even suicide.

According to Gong, the results show that the relationship between segregation and mortality is consistent and powerful, suggesting that social inequality is deeply embedded in the structure of American communities.

A map of privilege and peril

To quantify segregation, Gong used a measure known as the Index of Concentration at the Extremes (ICE). This metric captures how separated rich and poor, as well as White and Black, populations are within a given area. It ranges from negative values, representing areas where poor Black residents are concentrated, to positive values, representing areas dominated by affluent White residents.

By dividing all US counties into five ICE quintiles, from the most deprived to the most privileged, the study found a striking gradient. In the most deprived counties, the average age-adjusted mortality rate was 980 deaths per 100,000 people, compared to 703 deaths per 100,000 in the most privileged counties. This corresponds to a 32% higher risk of death in the most segregated areas.

The pattern was clear across all 11 leading causes of death from cardiovascular diseases and cancer to chronic respiratory illnesses, Alzheimer’s, kidney disease, influenza, pneumonia, diabetes, accidents, suicide and COVID-19.

Segregation’s deadly legacy

Segregation, both racial and economic, has long been a defining feature of American urban life. Decades of discriminatory housing policies, redlining, and unequal access to education and healthcare have created neighbourhoods where deprivation and privilege exist side by side, yet worlds apart.

The study shows that segregation amplifies disadvantage. Counties in the most deprived quintile were more likely to be rural, have higher unemployment and lower average incomes, and a much larger proportion of Black residents. In these areas, poor access to healthcare, lower educational attainment and environmental stressors combine to shorten lives.

Meanwhile, the most privileged counties, often found in parts of the Northeast and West, such as California and Colorado, benefit from better infrastructure, healthcare and economic stability. These counties are also more urbanised, with a higher proportion of affluent White residents and significantly lower mortality rates.

When race and income collide

Previous studies have examined either racial or economic segregation independently. However, Gong’s research highlights that the combination of race and income tells the full story. When both dimensions were analysed together using the ICE for race plus income, the association with mortality became even stronger than when race or income were studied separately.

Counties with high racial segregation but moderate income differences showed smaller variations in death rates. But when poverty and race overlapped, for example, predominantly Black counties with low household incomes, mortality rates soared. The study revealed that the combined ICE measure produced the strongest effect size, a Cohen’s d value of 2.14 between the most deprived and most privileged counties, far exceeding the effect size for race alone (0.69).

Where people live shouldn’t determine how long they live, yet our findings show that racial and economic segregation continues to shape life expectancy across the United States. Addressing these deep-rooted inequalities is essential for achieving true health equity.

-Rui Gong

The geography of inequality

Visual maps from the study present a sobering picture of America’s health geography. Counties in the Southeast and parts of the Midwest regions, historically shaped by racial segregation and poverty, are the most deprived and record the highest mortality rates. Conversely, counties in the Northeast and West exhibit higher socioeconomic status and better health outcomes.

These patterns suggest that historical and systemic inequities continue to dictate health outcomes, even decades after civil rights reforms. Structural segregation, Gong argues, remains a silent but powerful driver of health inequality.

The analysis also showed that urbanisation influences the strength of this relationship. Rural counties tended to be more deprived, while urban counties were more privileged. This urban–rural divide adds another layer to the mortality gap, reflecting differences in access to hospitals, education, and social mobility.

Beyond numbers: What policies can do

The implications of these findings are urgent. Gong and colleagues emphasise that reducing mortality disparities requires addressing the spatial roots of inequality. Policies that promote equitable urban planning, invest in underserved communities, and improve access to healthcare and education are essential to break the link between segregation and premature death.

Public health programmes must also account for structural factors, not just individual behaviours. As Gong points out, even the healthiest lifestyle cannot offset the risks created by systemic neglect, environmental hazards, and disinvestment in segregated areas.

Equity-oriented policies could include incentives for mixed-income housing, anti-redlining enforcement, expansion of community healthcare services, and investment in minority neighbourhoods. Gong argues that tackling segregation should be seen as a public health intervention, not merely a social reform.

Why ICE matters

The study’s use of the Index of Concentration at the Extremes represents a methodological advance in public health research. Traditional measures often fail to capture the dual impact of race and income. ICE provides a more nuanced view by representing both extremes from deprivation to privilege within a single scale.

By applying this measure to over 3,000 counties and adjusting for demographic and geographic variables, the analysis revealed robust, statistically significant trends (p < 0.001 across all models). The use of mixed-effects models also accounted for clustering effects at the regional level, thereby improving accuracy.

As the United States faces growing economic inequality, public health experts argue that addressing segregation is one of the most powerful ways to improve population health. The challenge now is translating evidence into policy.

Gong’s study raises an unsettling yet essential question: Can America close the health gap without first addressing the segregation gap?

Reference

Gong, R. (2025). Relationship between residential racial and economic segregation and main causes of death in US counties. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-025-02367-z