In the opening minutes of Netflix’s Adolescence, 13-year-old Jamie Miller is jolted awake by police storming his childhood bedroom. His space-themed wallpaper, stuffed toys, and bewildered expression clash violently with the accusation: murder. The scene, visceral and jarring, mirrors a grim reality. Weeks before the show’s release, an 11-year-old in Lynnwood, Washington, was arrested for attempting to stab a classmate. Fiction and reality are converging, and the question lingers: Why are children committing such acts?

The answer, experts argue, lies at the intersection of adolescent psychology, digital radicalisation, and systemic failures. For researchers and educators, Adolescence is not just a crime drama—it’s a case study in modern teen vulnerability.

The science of teenage vulnerability

Adolescence is a biological crucible. The brain’s reward system matures faster than its prefrontal cortex, which governs impulse control. This mismatch, paired with shifting circadian rhythms, primes teens for risk-taking. Dr Caroline Fenkel, chief clinical officer at Charlie Health, explains: “Teens are evolutionarily wired to seek thrills. Without support, they gravitate toward anything offering power or belonging, even toxic ideologies.”

Loneliness exacerbates this risk. A 2021 survey by the Survey Center on American Life found 25% of men under 30 have no close friends. For boys like Jamie, isolated and adrift, online communities fill the void, often with dangerous consequences.

Digital danger: The rise of the ‘manosphere’

Adolescence spotlights the “manosphere,” a network of forums, influencers, and podcasts promoting misogyny. Jamie’s descent begins with coded emojis: a red pill (symbolising anti-feminist “enlightenment”) and a dynamite (cyberbullying). These symbols, trivial to adults, are gateways to extremist rhetoric.

Real-world parallels abound. Andrew Tate, arrested in 2023 on human trafficking charges, remains a “hero” in these spaces. His content, which frames dominance as masculinity, reaches millions of teens. A 2024 Pew Research study found 46% of US teens are online “almost constantly”, a statistic that terrifies educators. “Algorithms push kids into rabbit holes,” says Emily Cherkin, a Seattle-based screentime consultant. “One click on a fitness video can lead to red-pilled content within hours.”

Social-emotional learning: A shield against crisis

Schools are frontline defences, yet resources are strained. Social-emotional learning (SEL) programmes teaching stress management, empathy, and conflict resolution have proven effective. A 2023 meta-analysis of 400+ global studies linked SEL to reduced suicide ideation and improved academic performance.

But political backlash threatens progress. In the US, lawmakers have branded SEL “divisive,” conflating it with critical race theory. Karen VanAusdal of the Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL) argues this misunderstands SEL’s goal: “It’s not ideology. It’s teaching kids to cope with emotions, skills they desperately need.”

Parents, educators, and the decoding dilemma

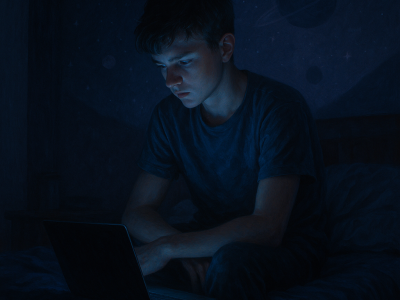

Jamie’s parents, portrayed as loving but oblivious, symbolise a generational divide. They monitor his physical safety but miss digital threats. “Parents think ‘my child is home, so they’re safe’,” says Cherkin. “But a smartphone in their bedroom is a 24/7 portal to danger.”

Teachers, too, struggle. Jennifer Greif Green, a child psychologist at Boston University, notes educators often spot behavioural shifts first. “They see 30 kids daily. A withdrawn student stands out.” Yet secondary school teachers rarely receive training to address mental health, a gap that leaves teens like Jamie slipping through cracks.

Policy and prevention: A path forward

The series’ release coincides with UK Prime Minister Keir Starmer’s push to address “bedroom radicalisation.” In January 2025, he warned of lone actors “consuming extremist content online.” Solutions are emerging:

- School screenings: Adolescence is now free for UK schools, sparking discussions on toxic masculinity.

- Tech delays: The Smartphone Free Childhood Pact urges parents to withhold smartphones until age 14.

Legislation lags, however. While the UK reports a 4.4% annual rise in knife crimes among teens, funding for youth mental health services remains inconsistent.

Bridging science and society

Adolescence ends without easy answers. Jamie’s fate is ambiguous, but the message is clear: societal change is urgent. Dr Gregory Moy, a clinical psychologist, stresses, “Adults must model behaviour, set boundaries, and critically listen without judgement.”

For researchers, the series underscores a duty to translate findings into accessible tools. SEL curricula, parent guides, and policy briefs must reach beyond academia. As Fenkel notes, “Teens aren’t broken. The systems around them are.”

The show’s haunting final scene lingers: Jamie’s father weeping, whispering, “Where did I fail?” The answer lies not in blame, but in collective action. Will we invest in mental health resources, reform tech algorithms, and prioritise SEL, or let the next generation navigate this chaos alone?