In the small fishing town of Minamata, Japan, in the 1950s, locals began experiencing unusual symptoms. They stumbled, lost coordination, and struggled to speak or see clearly. Soon, what seemed like isolated incidents spiralled into a catastrophe, and families helplessly watched their loved ones deteriorate without knowing why. What they did not realise was that their seafood, a staple of their daily diet, was poisoning them slowly, quietly, and irrevocably.

Minamata disease, a severe neurological disorder caused by mercury poisoning, first came to global attention through this tragedy. It remains one of the world’s most harrowing examples of industrial pollution. Recent research published by Dr. Yuki Nakamura in the “Journal of Environmental Toxicology and Public Health” from Kyushu University sheds new light on the far-reaching implications of mercury contamination, underlining the persistent relevance of Minamata’s painful lessons.

From abundance to anguish

Minamata’s economy depended largely on fishing. The waters of Minamata Bay were abundant and seemed pristine. However, hidden beneath the sparkling surface, chemical giant Chisso Corporation was discharging wastewater containing methylmercury directly into the bay. This toxic compound accumulated in marine life, eventually entering the human food chain.

The first symptoms appeared quietly but escalated dramatically. Patients exhibited numbness in limbs, loss of peripheral vision, hearing impairment, speech disorders, and eventually, paralysis and death. Nakamura’s research underscores that methylmercury’s neurotoxicity was not only swift but also devastatingly irreversible, affecting thousands and killing hundreds.

Initially, doctors were baffled. They misdiagnosed symptoms as isolated neurological conditions. The delay in identifying mercury poisoning allowed the disaster to worsen unchecked, highlighting gaps in medical knowledge and the regulatory oversight at that time.

Science behind the suffering

Minamata disease is primarily caused by methylmercury, a potent neurotoxin. Unlike elemental mercury, methylmercury easily crosses the blood-brain barrier, severely damaging neurons. Once in the body, it targets the central nervous system, causing neurological degradation.

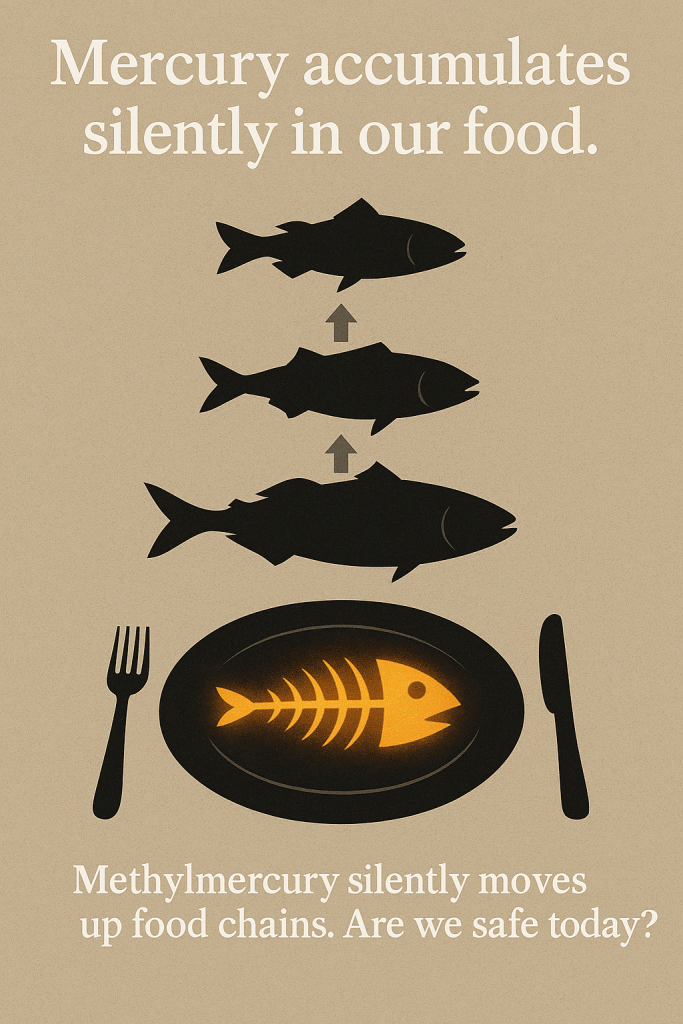

Research published by Nakamura emphasises the compound’s bioaccumulative properties. Small marine organisms absorbed methylmercury first, and larger predators consumed these organisms, magnifying the toxin up the food chain—a process scientists call biomagnification. Consequently, fish such as tuna and mackerel, vital to local diets, became hazardous sources of mercury poisoning.

Methylmercury exposure is particularly harmful during pregnancy, severely affecting foetal development. The condition known as Congenital Minamata disease afflicted newborns, causing cerebral palsy-like symptoms, severe cognitive impairment, and lifelong disability. These children became the tragic symbol of industrial negligence.

The photographs that shocked the world

The global awakening to Minamata’s plight came significantly from the work of American photographer W. Eugene Smith. His poignant images of victims, particularly the iconic “Tomoko Uemura in Her Bath,” profoundly moved public opinion worldwide.

Smith’s photographs, capturing the raw human tragedy, transformed Minamata from an isolated event into a global symbol of environmental justice. The international outrage forced Chisso Corporation and the Japanese government to acknowledge the magnitude of the disaster and begin restitution and regulation.

Lessons learned but challenges remain

Decades later, Minamata disease’s impact persists. Nakamura’s findings highlight long-term environmental contamination, affecting communities even generations later. Mercury contamination of Minamata Bay remains, despite extensive clean-up efforts. Persistent pollution continues to pose risks, and new cases occasionally emerge, underscoring the toxin’s stubborn legacy.

Moreover, Minamata influenced global policy profoundly. The disaster directly inspired the Minamata Convention on Mercury, an international treaty aiming to reduce mercury emissions. Ratified by numerous countries, the treaty represents significant progress towards preventing future mercury poisoning.

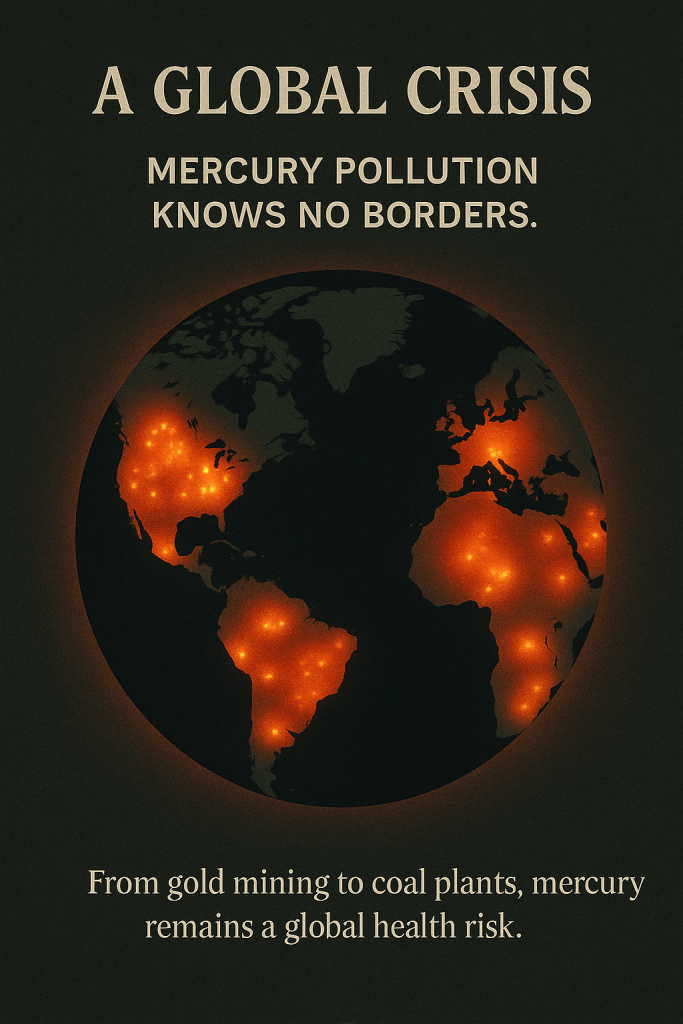

However, industrial mercury emissions continue globally, notably from artisanal gold mining and coal burning. Developing nations remain vulnerable due to weaker environmental regulations. As global industries expand, Minamata’s painful history serves as a stark reminder that economic growth should not come at the expense of environmental health and human dignity.

Mercury's global resurgence

Mercury poisoning is not confined to history. Recent studies highlighted by Nakamura show increasing mercury levels in regions around the Amazon Basin, where illegal gold mining operations proliferate. Mercury, used to separate gold from ore, pollutes rivers and fish populations, threatening indigenous communities reliant on these resources.

Similarly, coal-powered industries in China and India continue releasing mercury into the atmosphere, spreading contamination globally. Nakamura’s research advocates stringent international collaboration and regulatory action to mitigate these threats, emphasising that mercury knows no borders.

Connecting the past to present

Understanding Minamata disease helps contextualise contemporary environmental crises. Just as mercury silently invaded Minamata’s food chain, today’s invisible pollutants—like microplastics and persistent organic pollutants—enter ecosystems worldwide. Nakamura suggests Minamata disease exemplifies the catastrophic consequences when corporate accountability and environmental oversight fail.

The parallels are clear: pollution, unchecked industrial activities, and delayed governmental responses repeatedly endanger communities worldwide. Minamata’s tragedy challenges humanity to reflect critically on how industry, government, and society interact.

Beyond blame, towards accountability

One significant outcome from Minamata disease is the reinforced notion of corporate and governmental accountability. In the 1960s, Chisso Corporation faced legal consequences, but it took decades for victims to receive substantial compensation. This drawn-out process highlights the need for quicker, more effective justice mechanisms.

Nakamura argues that contemporary governments and industries must prioritise transparent environmental monitoring and rapid response strategies. Effective oversight can significantly mitigate risks, preventing future tragedies.

Today, environmental advocacy groups worldwide echo Minamata’s story in their fight for stricter pollution controls and improved industrial transparency. Nakamura’s research calls for a broader social responsibility where corporations proactively prioritise environmental protection, demonstrating that profitability and environmental stewardship can coexist sustainably.

The urgent need for global vigilance

The story of Minamata disease serves as a powerful reminder of humanity’s fragile relationship with the environment. Nakamura’s ongoing research insists that preventing similar disasters requires constant vigilance, informed policy-making, and international cooperation.

As climate change accelerates environmental degradation and industries expand into fragile ecosystems, understanding Minamata’s legacy is more critical than ever. Nakamura’s call for global action emphasises that the true measure of progress lies not in economic gain alone but in safeguarding public health and ecological integrity.

Will history repeat itself?

Minamata’s enduring lesson poses an essential question: have societies truly learned from this catastrophic mistake? While progress is evident, Nakamura’s findings remind readers that risks persist. Mercury contamination remains an ongoing global health issue, requiring persistent attention and international cooperation.

The case of Minamata disease continues to compel societies worldwide to critically assess industrial practices. Ultimately, the answer to whether humanity has genuinely absorbed these lessons depends on collective vigilance, regulatory enforcement, and a commitment to sustainable development.

Are we prepared to ensure such tragedies never recur? The decision lies collectively with governments, industries, and individuals—each holding a share of responsibility for the health of our shared environment and future generations.

References

- Nakamura, Y. (2025). Methylmercury exposure and neurological outcomes in Taiji residents. Journal of Environmental Toxicology and Public Health, 39(2), 123–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvtph.2025.02.005

- Ekino, S., Susa, M., Ninomiya, T., Imamura, K., & Kitamura, T. (2007). Minamata disease revisited: An update on the acute and chronic manifestations of methyl mercury poisoning. Journal of the Neurological Sciences, 262(1–2), 131–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jns.2007.06.036

- Sakamoto, M., Marumoto, M., Haraguchi, K., Toyama, T., Saito, Y., Balogh, S. J., Tohyama, C., & Nakamura, M. (2025). Assessing the role of selenium in Minamata disease through reanalysis of historical samples. Environment International, 195, 109242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2024.109242

- Harada, M. (1995). Minamata disease: Methylmercury poisoning in Japan caused by environmental pollution. Critical Reviews in Toxicology, 25(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.3109/10408449509089885

- National Institute for Minamata Disease (NIMD). (n.d.). Research activities. Retrieved from https://nimd.env.go.jp/english/kakubu/kiso/fujimura.html