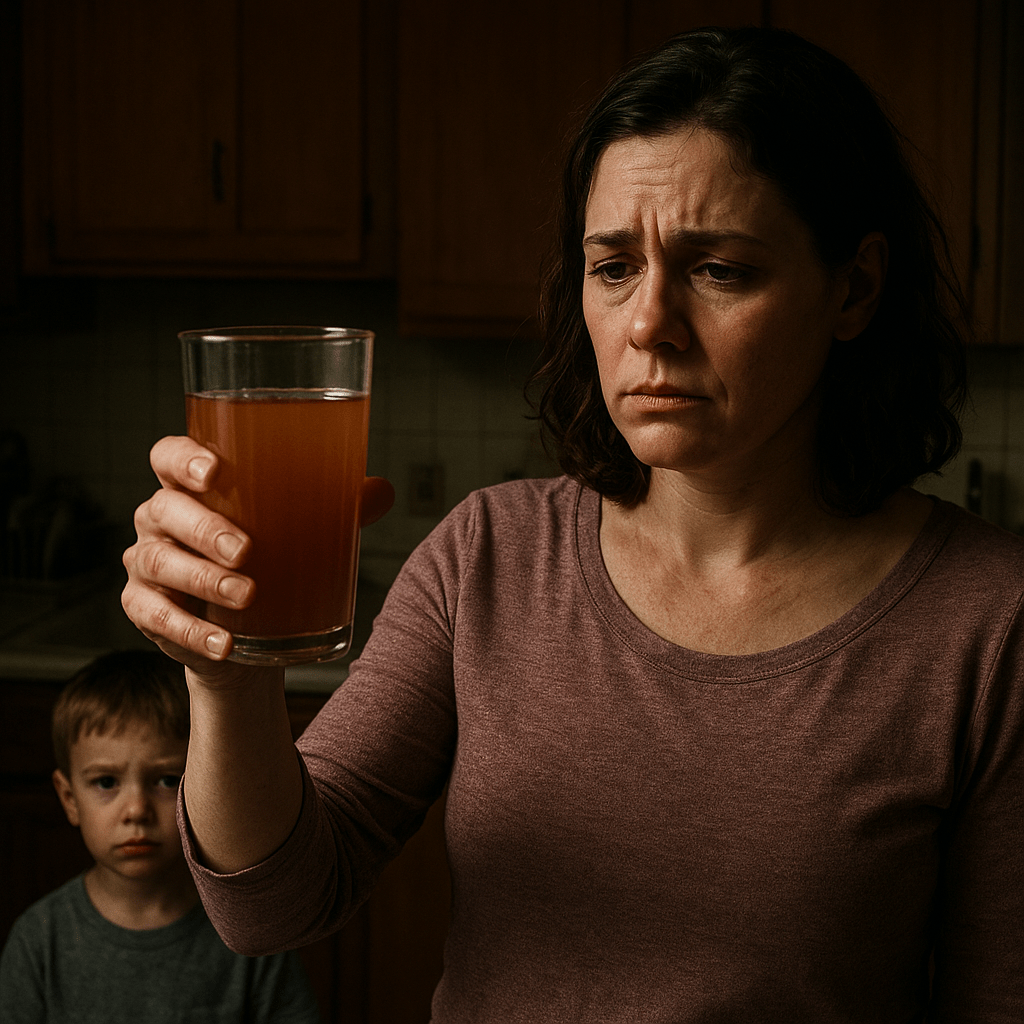

On a hot summer day in 2014, a mother in Flint, Michigan, poured a glass of tap water to cool her child. Instead of crystal-clear relief, a rust‑coloured liquid filled the cup. She thought it was a plumbing quirk. But that single glass would unravel a deeper threat. The Flint water crisis emerged not as a general failure of infrastructure, but as a case study in environmental injustice tied to cost‑cutting and scientific negligence.

Flint was once the beating heart of America’s automotive industry. But by 2014, it had become a symbol of economic decline and shrinking population. The city had long been drawing safe, treated water from Lake Huron via the Detroit system. Yet mounting budget pressures led emergency managers, appointed under a state law for financially troubled cities, to seek drastic savings by sourcing water from the Flint River.

The switch that started it all

On 25 April 2014, Flint officially switched to Flint River water. The river’s water was more corrosive, but the authorities failed to add anti‑corrosion chemicals. Within weeks, residents began reporting brown tap water that smelled of bleach and made people ill. Yet officials repeatedly assured them the water was safe.

General Motors, however, noticed that the river water was corroding engine parts and reverted to Detroit water in January 2015. Flint residents did not receive the same fix.

Early warnings ignored

Throughout early 2015, local health professionals began sounding the alarm. Doctors reported rashes, infections, and other ailments that coincided with the water switch. It took until July for Virginia Tech engineer Professor Marc Edwards, and local campaigner LeeAnne Walters to bring attention to the high lead content in tests taken from household taps.

Dr Mona Hanna-Attisha, Paediatric residency director at Hurley Medical Center, conducted her own peer‑reviewed study. The research, published in American Journal of Public Health (2015), showed lead levels in children’s blood had nearly doubled from 2.4 % to 4.9 % after the water source was switched

Turning point

Dr Hanna’s findings, initially dismissed by officials, prompted national headlines and community outrage. The state eventually admitted the data were correct. On 16 October 2015, Flint switched back to the Detroit‑sourced water, though the corrosion damage had already happened.

In January 2016, Michigan declared a state of emergency followed by a federal declaration by President Obama. The United States House of Representatives authorised funds and investigations into potential criminal wrongdoing.

Public health impact: More than just water

Lead is a dangerous neurotoxin. There is no known safe level of exposure for children. High exposure during development is linked to reduced IQ, difficulties in attention and behaviour, impaired academic performance, and even increased incarceration rates later in life.

A 2024 study in Science Advances, led by Sam Trejo, Gloria Yeomans‑Maldonado and Brian Jacob documented significant impacts on children’s educational outcomes affected cohorts had lower test scores, attendance rates fell, and high school graduation rates dropped.

A federal court mandated a comprehensive lead service‑line replacement programme in 2016. As of mid‑2025, over 97 % of lead service pipes in Flint have been replaced, marking a major milestone.

In May 2025, the Environmental Protection Agency lifted its emergency water order after nine consecutive years of passing safety tests. Yet, many residents remain cautious.

The national ripple effect

In October 2024, under President Biden, the EPA introduced the final Lead and Copper Rule Improvements, mandating removal of all lead service lines nationwide within ten years, supported by $2.6 billion in federal infrastructure funding and tighter testing protocols.

These regulations take direct lessons from Flint’s failures. More than 9 million lead pipes still serve American households, often in low‑income communities, mirroring the environmental racism evident in Flint.

Legal repercussions have been complex and prolonged. In February 2024, Flint reached a $25 million settlement with engineering firm Veolia North America. Meanwhile, criminal charges have touched dozens of officials, but top administrators largely avoided prosecution.

The 2020 $600 million settlement was another financial milestone, focused on compensating affected children and residents.

Healing the social fabric

Tackling the lifelong impacts of lead poisoning requires more than replacing pipes. Flint initiated nutrition programmes to help children with calcium‑rich and vitamin‑C diets, which help reduce lead absorption.

Dr Hanna‑Attisha also pioneered RX Kids, a programme offering direct payments to Flint mothers to combat poverty and improve child development outcomes. Studies show this model can reduce food insecurity and enhance early childhood health.

Despite nearly completed pipe replacement work, Flint’s water system remains financially fragile. The city lost close to 20 % of its population since 2014, shrinking its tax base and complicating water funding.

Residents continue filtering their water and express frustration at being excluded from national recovery conversations.

What comes next for flint?

As the world takes note, it is critical to ask: Will Flint be a lesson or a warning? With pipe replacement nearly complete and federal guidelines strengthening, the next steps lie in sustained monitoring, health support for affected individuals, and robust financial models for water utilities.

A new wave of research is emerging: a 2025 study from Harvard’s T.H. Chan School of Public Health will examine the lifelong developmental impacts on Flint’s youth. Yale University is tracking long‑term birth outcomes. Both are crucial to understanding how toxic exposure alters life trajectories.

Flint’s poisoned water glass is now empty, but its legacy continues.

Here is the question for us all: In a world still filled with neglected pipes and marginalised neighbourhoods, are we ready to make Flint the turning point or will we let history repeat itself?

Reference

Hanna-Attisha, M., LaChance, J., Sadler, R. C., & Champney Schnepp, A. (2016). Elevated blood lead levels in children associated with the Flint drinking water crisis: a spatial analysis of risk and public health response. American journal of public health, 106(2), 283-290. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2015.303003

Trejo, S., Yeomans-Maldonado, G., & Jacob, B. (2024). The Effects of the Flint water crisis on the educational outcomes of school-age children. Science Advances, 10(11), eadk4737. https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.adk4737