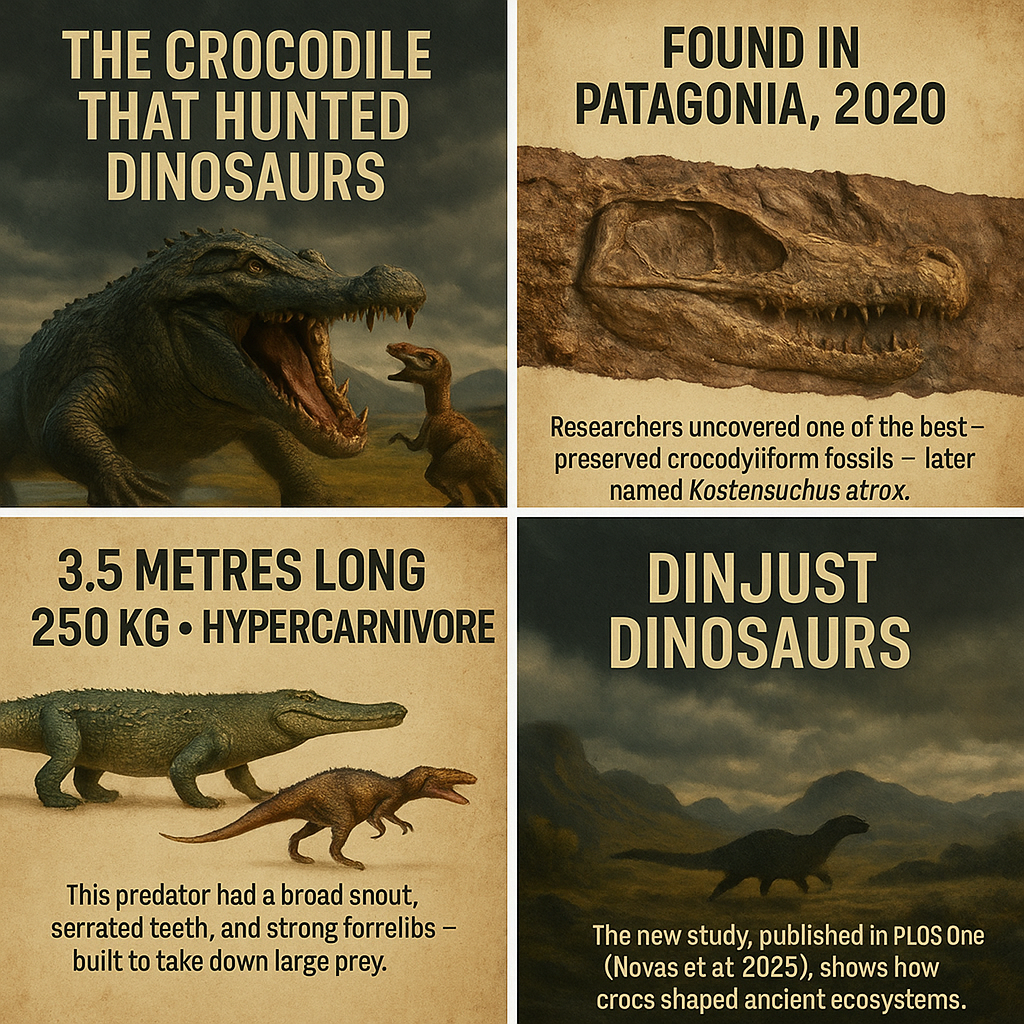

Seventy million years ago, Patagonia was home to more than just dinosaurs. According to new research, the region also hosted a formidable crocodile-like predator that could rival dinosaurs in size and ferocity. The reptile, named Kostensuchus atrox, belonged to an extinct lineage of crocodyliforms and is now recognised as one of the most complete specimens of its kind ever unearthed.

The discovery, published in PLOS One, was led by Fernando E. Novas of the National Scientific and Technical Research Council (CONICET) in Argentina, alongside an international team of palaeontologists. Their study describes in unprecedented detail how this hypercarnivorous reptile may have competed directly with dinosaurs for dominance in late Cretaceous ecosystems.

A predator with power and presence

The fossilised remains were recovered in 2020 from the Chorrillo Formation near El Calafate in southern Patagonia. Encased in a large concretion, the skeleton included a beautifully preserved skull, jaws, vertebrae, ribs, and robust forelimbs.

Based on the remains, Kostensuchus atrox grew to around 3.5 metres (11.5 feet) in length and weighed an estimated 250 kilograms (550 pounds). This makes it one of the largest crocodyliform predators of its time, second in size only to the local megaraptorid theropod Maip macrothorax, a dinosaur that reached nine metres in length.

Unlike modern crocodiles, which are tied closely to rivers and wetlands, K. atrox was adapted to life on land. Its broad snout, ziphodont (serrated) teeth, and deep lower jaw were well suited for slicing through the flesh of large prey. The study classifies it as hypercarnivorous, meaning that more than 70% of its diet consisted of meat.

The meaning behind the name

The name Kostensuchus atrox blends cultural, geographic and mythological references. “Kosten” comes from the word for the powerful Patagonian wind. “Suchus” derives from Sobek (Suchus), the crocodile-headed Egyptian god of power and ferocity. The species epithet “atrox” means “harsh” in Greek.

Together, the name encapsulates both the formidable natural environment of Patagonia and the predator’s fearsome role within it.

The broad and high snout of Kostensuchus atrox, with notably large and robust teeth, along with a deep mandibular ramus and strong forelimbs, suggests that this species was capable of subduing large prey.

-Dr. Novas and colleagues reported in their paper

Challenging dinosaurs for dominance

Popular imagination often places dinosaurs as the uncontested rulers of the Mesozoic. Yet the fossil record increasingly reveals a more competitive picture. Alongside theropods, broad-snouted crocodyliforms like K. atrox occupied roles as apex predators.

The skull of K. atrox was short and wide compared with narrow-snouted relatives. Its enormous fourth dentary tooth interlocked with upper jaw caniniforms, while its serrated cutting edges suggest a capacity to pierce and shear flesh efficiently. These adaptations indicate it was capable of tackling prey much larger than itself, including young or mid-sized dinosaurs such as hadrosaurs or ornithopods known from the same formation.

Phylogenetic analyses in the study confirm that K. atrox belonged to the peirosaurids, a group of crocodyliforms common in Gondwana (South America, Africa and Madagascar) during the Cretaceous. Remarkably, K. atrox represents the southernmost and geologically youngest record of this clade, placing it at the ecological forefront just before the asteroid impact that ended the age of dinosaurs.

A land of crocodiles

The late Cretaceous in South America has often been described as a “land of crocs.” Fossil evidence shows that crocodyliforms diversified into a variety of ecological roles, from small herbivores to large predators.

In Patagonia’s Chorrillo Formation, K. atrox shared its environment with dinosaurs such as the titanosaur Nullotitan glaciaris, the megaraptorid Maip, and several ornithischian species. Mammals, turtles, fish and early birds also thrived in this ecosystem. By analysing faunal associations, Novas and colleagues argue that broad-snouted crocodyliforms were not marginal players but keystone predators that shaped community structures.

Intriguingly, the fossil record shows regional differences. While K. atrox and megaraptorids dominated southern Patagonia, northern regions such as the Neuquén Basin appear to have been ruled instead by abelisaurid theropods, with no evidence yet of large peirosaurids. This suggests that predator guilds varied significantly across Cretaceous South America.

Anatomy revealed in exquisite detail

The preservation of K. atrox allowed researchers to describe features rarely seen in other peirosaurids. Highlights from the study include:

- A 49 cm skull, heavily ornamented and shorter than in other relatives, giving it a powerful bite.

- Large serrated teeth (ziphodont dentition), nearly twice the size of those in narrow-snouted species.

- A robust humerus with a deep fossa and shelf, suggesting strong forelimb muscles for capturing or dismembering prey.

- A broad mandibular symphysis (jaw joint), the widest among known peirosaurids, further evidence of an animal adapted for high bite forces.

Such completeness provides palaeontologists with the first clear understanding of how broad-snouted peirosaurids were built and why they succeeded as hypercarnivores.

Competing predators: Peirosaurids and baurusuchids

The study also compared K. atrox with another group of South American crocodyliforms, the baurusuchids, which independently evolved hypercarnivory. While both groups shared adaptations such as large serrated teeth, their skeletal differences suggest different hunting strategies.

- Peirosaurids like K. atrox had shorter, broader snouts and robust forelimbs, possibly suited for ambush and grappling prey.

- Baurusuchids, in contrast, had deep, narrow skulls and more erect limb postures, indicating a different approach to predation.

This evolutionary convergence highlights how crocodyliforms diversified to occupy predator niches often assumed to be dominated exclusively by theropod dinosaurs.

Expanding our picture of ancient Patagonia

The discovery of K. atrox adds nuance to the picture of late Cretaceous Patagonia. It shows that the region’s ecosystems were not only home to iconic dinosaurs but also to apex reptilian predators that shaped the balance of life.

Patagonia’s fossil beds continue to be a treasure trove for scientists, revealing surprising complexity in faunal communities just before the catastrophic mass extinction 66 million years ago. For modern readers, the lesson is clear: dinosaurs may dominate headlines, but they lived alongside a variety of powerful competitors, including crocodile-like hunters whose legacy is only now being unearthed.

Reference

Novas, F. E., Pol, D., Agnolín, F. L., Carvalho, I. de S., Manabe, M., Tsuihiji, T., Rozadilla, S., Lio, G. L., & Isasi, M. P. (2025). A new large hypercarnivorous crocodyliform from the Maastrichtian of Southern Patagonia, Argentina. PLOS One, 20(8), e0328561. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0328561