When the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences announced the winners of this year’s Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences, Joel Mokyr, Philippe Aghion, and Peter Howitt, the committee highlighted a message that resonates profoundly in our age of artificial intelligence, green transitions, and digital upheaval: economic growth cannot be taken for granted.

Awarded “for having identified the prerequisites for sustained growth through technological progress,” the 2025 laureates illuminate a timeless question with renewed urgency, how do societies sustain innovation over centuries, rather than stagnating after short bursts of progress?

The long arc of progress

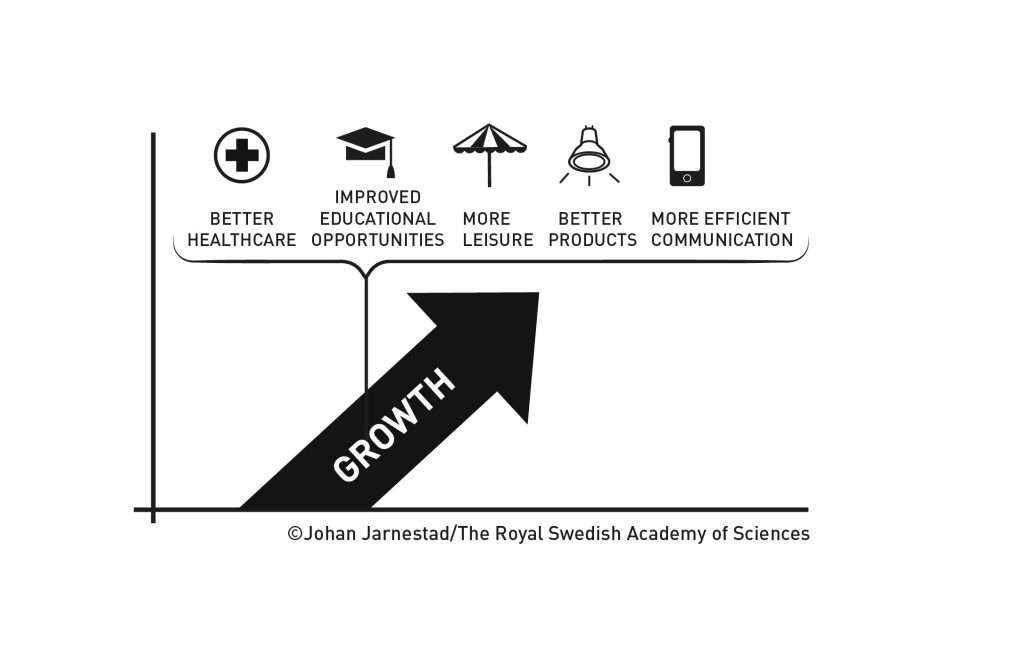

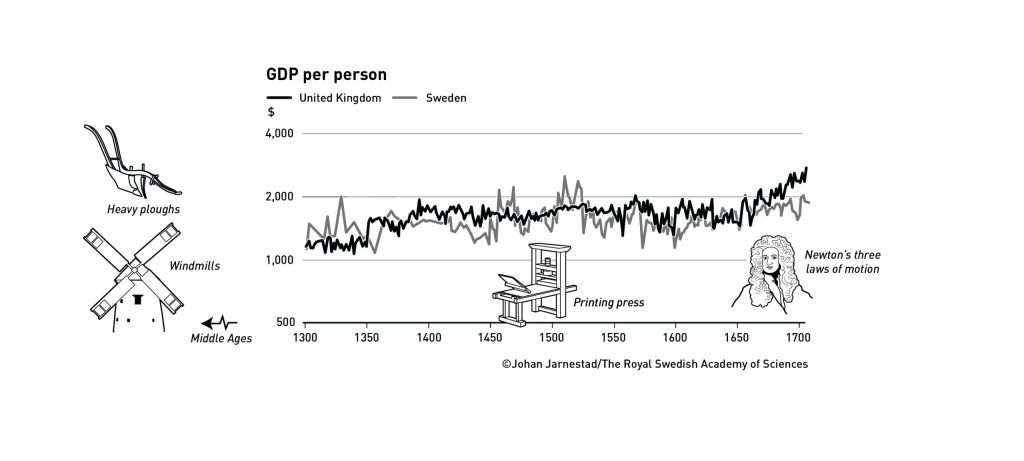

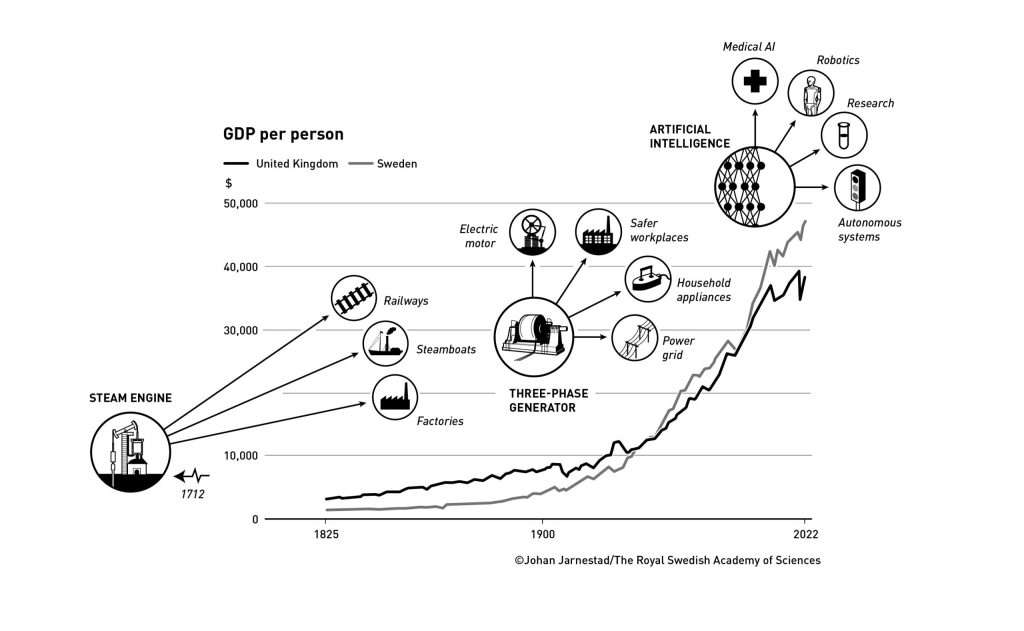

For most of human history, economic stagnation was the rule, not the exception. Occasional bursts of invention from irrigation to metallurgy improved life temporarily but rarely created lasting prosperity. The turning point came with the Industrial Revolution, when a self-sustaining cycle of innovation transformed economies across Europe and, eventually, the world.

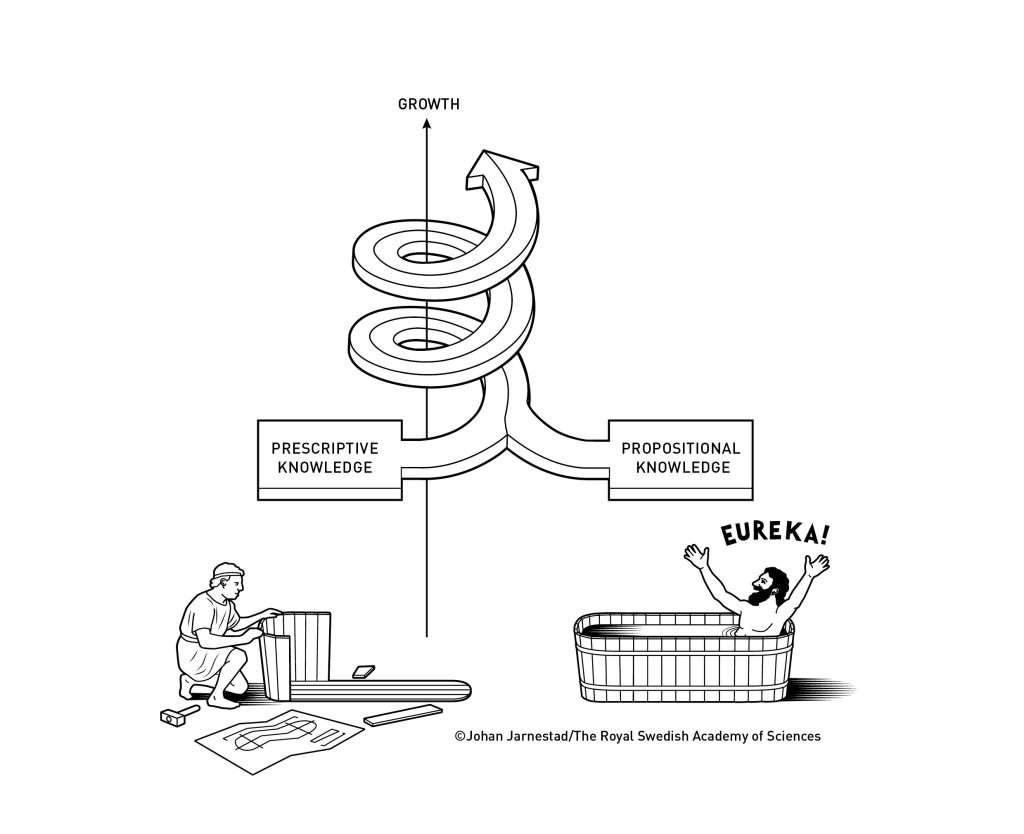

According to Joel Mokyr, Professor at Northwestern University, this transformation wasn’t simply a result of new machines. It was the outcome of a profound cultural and intellectual shift, a society that began to ask why things worked, not merely how to make them work.

Mokyr’s historical research traces how, from the seventeenth century onwards, scientific reasoning and openness to new ideas created fertile ground for continuous technological progress. In his view, innovation thrived when societies embraced curiosity, shared knowledge widely, and permitted dissent from established norms.

He argued that “for innovations to succeed one another in a self-generating process, we not only need to know that something works, but we also need to understand why.” Without that foundation, innovation stagnates, a lesson as relevant today as it was in the age of steam.

The mathematics of creative destruction

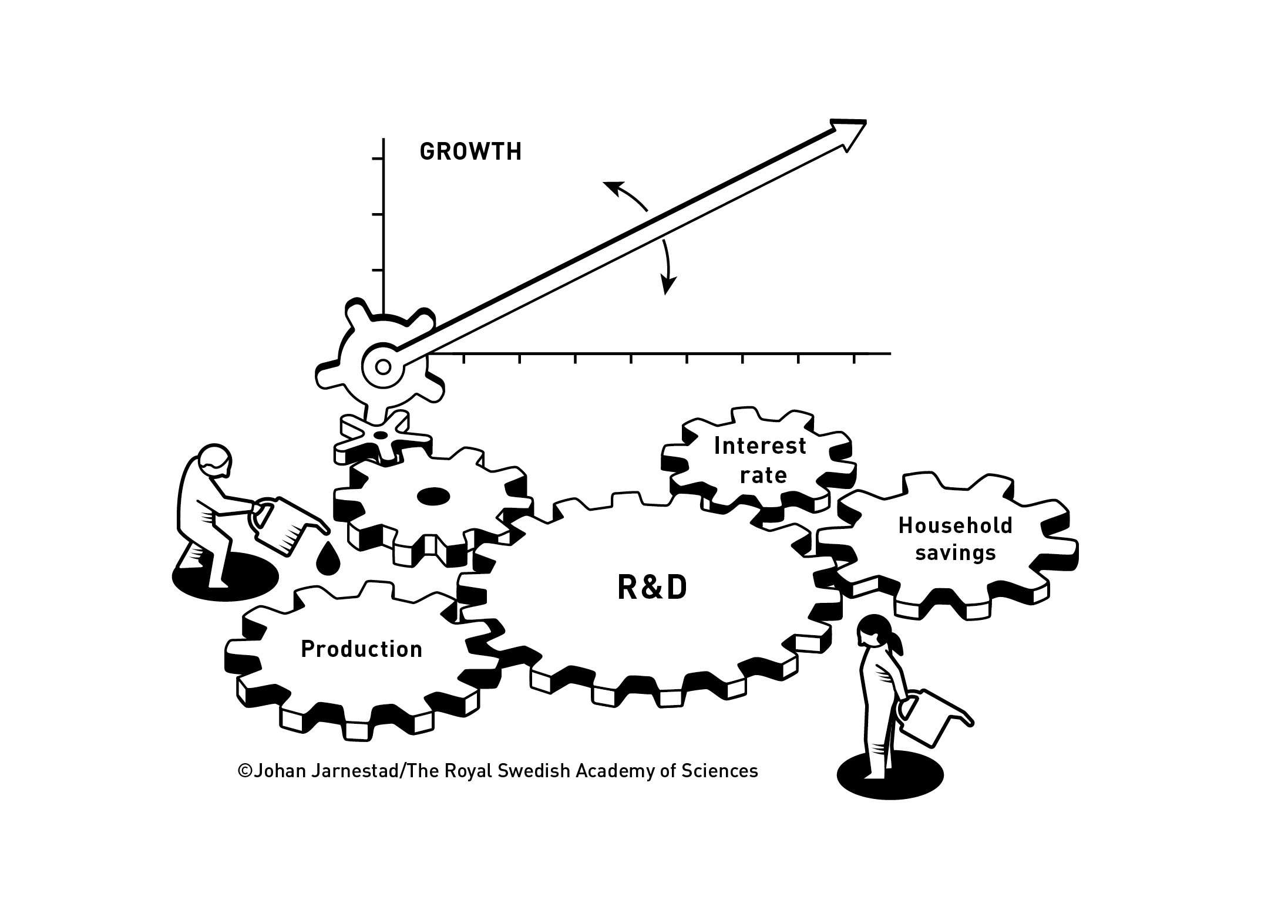

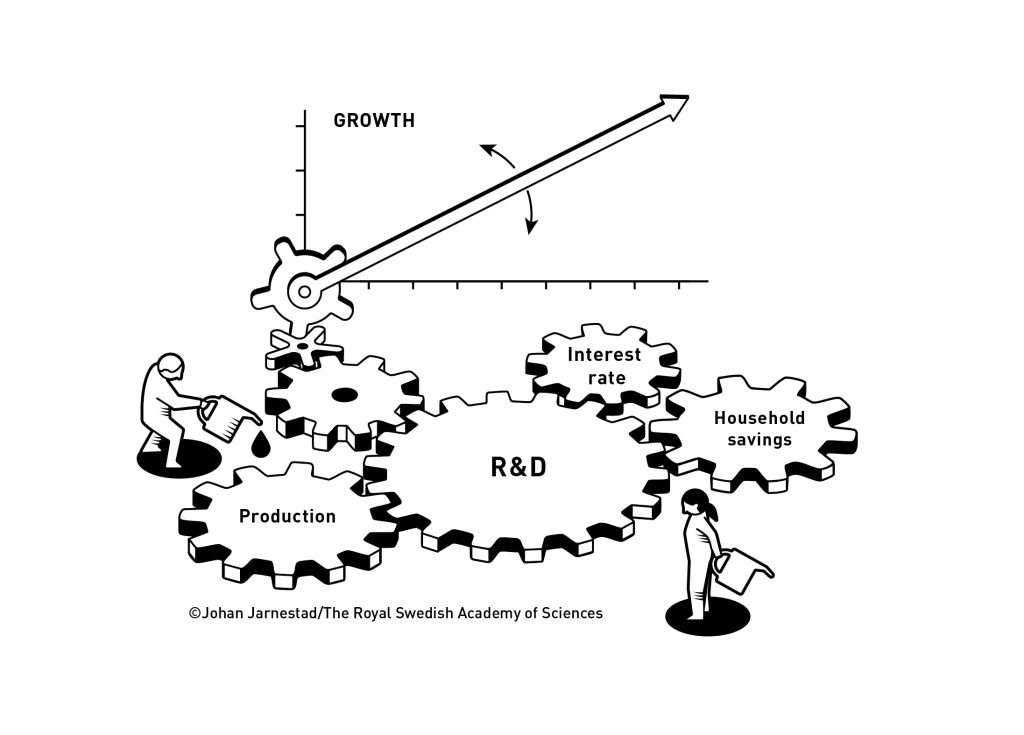

While Mokyr explored history’s cultural and intellectual drivers of growth, Philippe Aghion and Peter Howitt built the mathematical backbone that explains it.

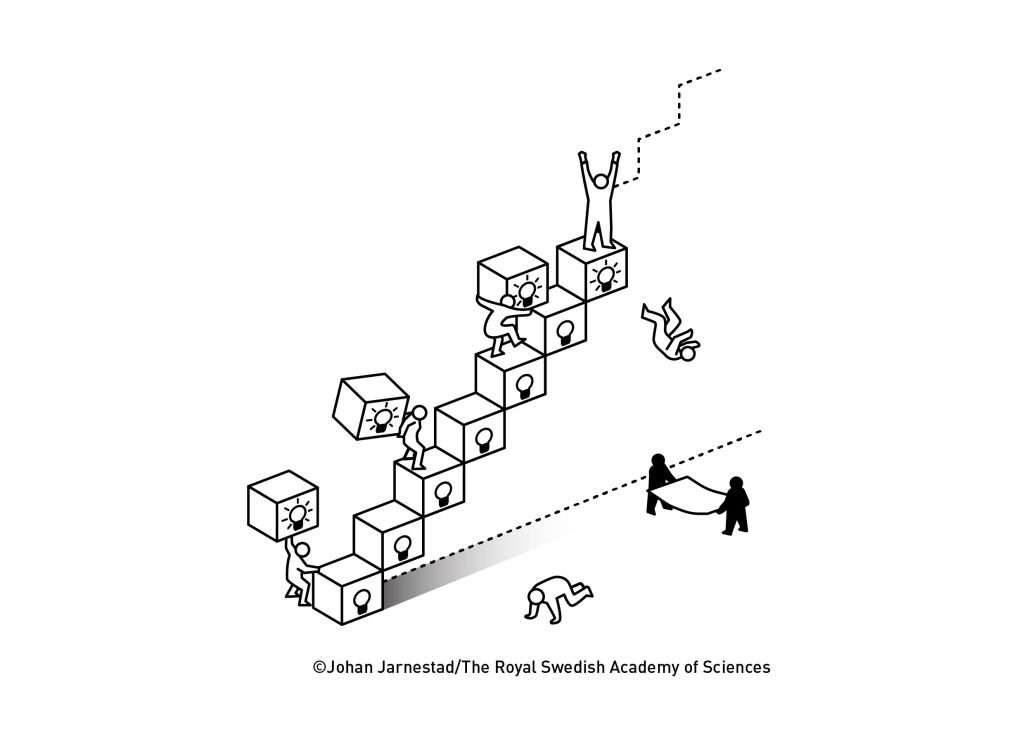

In their landmark 1992 paper, the duo developed a formal model of “creative destruction”, originally coined by economist Joseph Schumpeter. The theory describes how new technologies continuously replace older ones, creating both progress and disruption.

Their model showed that growth is not a smooth, linear process. Instead, it is a perpetual cycle of renewal, where innovation fuels productivity and prosperity, even as it displaces older firms, skills, and industries.

Aghion, now Professor at Collège de France, INSEAD, and the London School of Economics, and Howitt, Professor at Brown University, used this model to connect technological change with long-term growth, and to highlight the conflicts it produces.

Every innovation creates winners and losers. New entrants disrupt established players. Old industries resist change. Workers face transitions as new skills become essential and old ones obsolete. “Creative destruction,” in short, is both creative and destructive, and the balance between the two determines whether societies flourish or falter.

Innovation’s paradox: Progress through disruption

The Nobel Committee’s citation underscores a powerful message: innovation drives prosperity only when societies allow it to disrupt the status quo.

As John Hassler, Chair of the Prize Committee, remarked, “We must uphold the mechanisms that underlie creative destruction, so that we do not fall back into stagnation.”

The laureates’ work demonstrates that protecting incumbents from competition or discouraging experimentation can throttle long-term growth. Yet unregulated disruption can also deepen inequality and social unrest. The challenge, therefore, lies in balancing innovation with inclusion, a question policymakers continue to grapple with today.

From the spread of generative AI to the race for clean energy, the same dynamics play out. When new technologies arrive, established players resist, regulators hesitate, and workers worry. But societies that embrace experimentation, while cushioning the vulnerable through education and adaptation, ultimately gain the most.

Historical insight meets modern policy

Mokyr’s work, rooted in historical analysis, complements Aghion and Howitt’s theoretical contributions by showing why some societies foster innovation while others stagnate.

He found that growth flourishes where curiosity is rewarded, failure is tolerated, and new knowledge flows freely. His research draws attention to the institutions of progress such as universities, research academies, and networks of tinkerers and thinkers that underpin sustained innovation.

Meanwhile, Aghion and Howitt’s model provides a quantitative framework for understanding how these cultural and institutional conditions translate into measurable growth. Their later research extended the model to include the role of competition, education, and environmental policy, demonstrating that innovation-driven growth is inseparable from good governance and investment in human capital.

Together, their contributions reveal that technological progress is not an automatic outcome of scientific advancement; it depends on social openness, knowledge diffusion, and fair competition, all of which require careful policy design.

Creative destruction in the age of AI

Nowhere is the relevance of creative destruction clearer than in the unfolding revolution of artificial intelligence.

AI is disrupting industries at an unprecedented pace, from journalism and finance to manufacturing and healthcare. While it promises extraordinary productivity gains, it also poses deep questions about employment, inequality, and the ownership of technology.

Aghion and Howitt’s framework helps explain these dynamics: as AI tools enhance efficiency, they simultaneously render older systems obsolete. Firms that fail to adapt are displaced by leaner, more innovative competitors. The process mirrors Schumpeter’s vision and validates the laureates’ conclusion that innovation’s benefits hinge on society’s ability to adapt constructively.

Mokyr’s historical lens adds another layer: societies that fear change or suppress new ideas tend to stagnate. The AI age, therefore, will reward countries that invest in education, encourage competition, and remain intellectually open, rather than those that retreat into protectionism or nostalgia.

Balancing progress and protection

Yet innovation alone is not enough. Without fair redistribution, creative destruction can breed resentment. The laureates’ combined insights imply that economic policy must nurture innovation while cushioning disruption.

Aghion, in particular, has written extensively on the role of the state in enabling innovation-led growth. He argues for a “smart state”, one that invests in research, education, and infrastructure but avoids suffocating the entrepreneurial spirit.

Their ideas offer a roadmap for balancing market dynamism with social stability. The lesson is especially poignant as governments worldwide debate how to regulate AI, green industries, and digital platforms.

Innovation thrives when people feel secure enough to take risks. Policies that provide social safety nets, retraining programmes, and opportunities for mobility make creative destruction a force for collective progress, rather than social division.

A shared intellectual legacy

Though the laureates come from distinct disciplines, history, mathematics, and macroeconomics, their work converges on a single insight: progress is a process, not a product.

Joel Mokyr (born 1946 in Leiden, the Netherlands; PhD Yale University) brings the historical depth that reveals how past transformations unfolded.

Philippe Aghion (born 1956 in Paris; PhD Harvard University) and Peter Howitt (born 1946 in Canada; PhD Northwestern University) add the analytical precision that connects theory to policy.

Together, they bridge the gap between historical narrative and economic modelling, transforming how economists understand the engines of prosperity.

Lessons for an uncertain century

As the world confronts a century defined by climate change, demographic shifts, and rapid technological evolution, the laureates’ message feels almost prophetic.

Sustained growth will not come from preserving the old but from constantly reinventing the new. That means investing in science, fostering entrepreneurship, and cultivating openness to change, the very qualities that transformed Britain in the Industrial Revolution and Silicon Valley in the digital age.

But as Mokyr’s historical studies show, prosperity also depends on culture. Societies that fear disruption often stifle it. Those that tolerate dissent and celebrate discovery create the conditions for progress.

The 2025 Nobel in Economic Sciences thus celebrates not only three distinguished scholars but also the broader human spirit of innovation through understanding, the ability to ask “why” and not just “how”.

Profiles of the laureates

Joel Mokyr, born 1946 in Leiden, the Netherlands. PhD 1974 from Yale University, New Haven, CT, USA. Professor at Northwestern University, Evanston, IL, USA.

Philippe Aghion, born 1956 in Paris, France. PhD 1987 from Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA. Professor at Collège de France and INSEAD, Paris, France and The London School of Economics and Political Science, UK.

Peter Howitt, born 1946 in Canada. PhD 1973 from Northwestern University, Evanston, IL, USA. Professor at Brown University, Providence RI, USA.

Prize Amount: 11 million Swedish kronor (~1.2 millon USD), with one half to Joel Mokyr and the other half jointly to Philippe Aghion and Peter Howitt.

Reference

Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences. (2025). Nobel Prize in Economics 2025. https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/economic-sciences/2025/press-release/

Credit: Johan Jarnestad/The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences