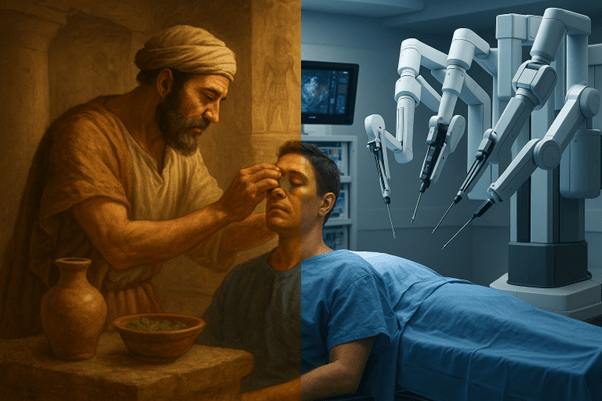

When a person loses their voice, struggles to breathe, or hears a persistent ringing in the ear, they turn to specialists in ear, nose, and throat (ENT) medicine. Today these specialists operate with robotics, artificial intelligence and nanotechnology. But thousands of years ago the story was very different. Healing relied on herbal pastes, sharpened stones, and crude instruments.

The history of ENT is one of the most remarkable journeys in science. It is a field that has always been about more than anatomy. It has been about restoring essential functions of life: breathing, speaking, hearing, and balance. These are the very senses through which humans connect with the world. A new article published in the Indian Journal of Otolaryngology and Head & Neck Surgery explores this long and complex history in depth. Their analysis not only traces the tools and techniques of ENT but also shows how societies have understood disease, managed suffering, and safeguarded human dignity.

This journey spans millennia, from ancient Egypt and India to the robotics-driven operating theatres of today. The story of ENT is also a story of resilience, curiosity, and humanity’s relentless desire to see, hear, and breathe more clearly.

Ancient cures and the first surgical skills

Records from ancient civilisations reveal some of the earliest attempts to treat ENT disorders. The Egyptian Ebers Papyrus, dating to around 1550 BCE, listed remedies for ear infections, nasal congestion and throat complaints. These treatments relied heavily on plant extracts and oils. While the scientific reasoning was limited, the therapeutic intent was clear. The early physicians recognised that the ear, nose and throat required targeted care.

In Greece, Hippocrates shifted medicine away from superstition. His insistence on careful observation and rational explanation of illness was revolutionary. His theories created the foundation for evidence-based practice. In India, the Sushruta Samhita went even further. Compiled around 600 BCE, it described advanced procedures such as rhinoplasty and tonsillectomy. These were highly technical interventions that required exceptional precision, centuries before anaesthesia or antisepsis were even imagined.

These traditions demonstrate that healing was seen as a holistic process. Illness was connected with lifestyle, environment, and spiritual balance. The contrast with many modern health systems is striking. Advanced as today’s techniques are, they sometimes risk fragmenting the patient into separate organs and conditions.

The medieval guardians of knowledge

The fall of the Roman Empire left Europe with a fragmented and often crude medical system. Barber surgeons performed minor procedures with little understanding of infection or anatomy. Yet the Islamic Golden Age preserved and expanded classical medical knowledge.

Avicenna’s Canon of Medicine became a central reference for centuries. Albucasis, known as the father of modern surgery, described detailed surgical instruments in his Al-Tasrif, including treatments for ear and throat disease. These texts were later translated into Latin and became essential for European physicians. Without these efforts, vast amounts of medical wisdom would have been lost.

Yet reverence for these authoritative texts created a paradox. They preserved knowledge but often discouraged questioning. Innovation slowed because challenging accepted wisdom was seen as a form of intellectual rebellion. This balance between tradition and innovation continues to shape medical culture today.

Renaissance rediscovery of anatomy

The Renaissance transformed medicine by reintroducing direct observation of the human body. Anatomists like Andreas Vesalius corrected centuries of errors in Galenic anatomy with his masterpiece De Humani Corporis Fabrica. His insistence on evidence from dissection set new standards for medical science.

At the same time, Ambroise Paré, a military surgeon, transformed battlefield surgery. His replacement of hot iron cauterisation with ligatures to control bleeding significantly reduced pain and mortality. His innovations were born out of necessity but went on to influence all areas of surgery, including ENT.

These developments show how societal forces such as war and empire often drove medical progress. ENT surgery was no exception. The demand for effective treatment of soldiers and civilians pushed physicians to rethink both technique and compassion.

The nineteenth century: Anaesthesia and antisepsis

The nineteenth century marked the dawn of modern surgery. The discovery of anaesthesia revolutionised medical practice. For the first time, surgeons could operate with accuracy and without the unbearable suffering that had previously defined surgical care.

Joseph Lister’s introduction of antisepsis was equally transformative. Carbolic acid sprays and aseptic methods reduced infection rates dramatically. This combination allowed ENT surgeons to attempt procedures previously considered too dangerous.

Technology also advanced rapidly. Friedrich Hofmann invented the otoscope in 1861, enabling doctors to visualise the ear canal. It was a small instrument with profound consequences. Physicians could now directly diagnose ear disease with precision. The otoscope remains an essential diagnostic tool even today.

Yet these innovations were not shared equally. Urban centres and wealthy patients benefited, while millions in rural or impoverished regions had little access. The pattern of unequal distribution of medical advances has persisted into the modern age.

The twentieth century: Seeing more, cutting less

The twentieth century introduced tools that changed ENT surgery fundamentally. Endoscopy enabled physicians to look deep inside the sinuses, throat, and larynx without large incisions. Paired with microsurgery, this allowed delicate structures to be operated on with far greater accuracy.

Functional Endoscopic Sinus Surgery, developed by Walter Messerklinger and later Wolfgang Stammberger, became a cornerstone treatment for chronic sinus disease. Patients experienced shorter recovery times and fewer complications. ENT entered an era where seeing more meant cutting less.

Yet innovation sometimes moved faster than evidence. Not every minimally invasive technique delivered long-term improvements. This highlighted the necessity of rigorous trials and critical evaluation. Medicine advances not only through invention but through constant reassessment of outcomes.

Robotics and artificial intelligence

The twenty first century has seen the arrival of robotics in ENT operating theatres. The Da Vinci Surgical System offers surgeons three dimensional views and tremor-free control of instruments. Complex operations of the throat, larynx, and thyroid can now be performed through small entry points rather than large incisions.

Research has demonstrated clear patient benefits. Robotic surgery can reduce blood loss, lower post-operative pain, and shorten hospital stays. However the technology is costly. Robotic systems can cost millions of pounds, and the training needed is intensive. For now, their use is concentrated in advanced hospitals, raising pressing ethical questions about fairness and global health equity.

Artificial intelligence is also changing ENT. Algorithms are being trained to interpret medical scans, identify tumours, and guide navigation during endoscopic procedures. These systems can support surgeons in real time, enhancing safety and precision. The integration of AI represents not only a technical advance but a fundamental shift in how surgery is conceptualised.

Bioprinting, nanotech, and the road ahead

Beyond robotics, ENT is being reshaped by developments in biotechnology. Nanotechnology is being tested for targeted drug delivery within the delicate structures of the ear and sinuses. This reduces side effects and ensures that treatment is concentrated exactly where it is needed.

Bioprinting is one of the most exciting frontiers. Researchers are exploring the possibility of printing tissues such as cartilage for reconstructive surgery. The implications for conditions requiring nasal or laryngeal reconstruction are immense. Augmented and virtual reality are also becoming powerful tools for training and surgical planning. Surgeons can rehearse complex operations in simulated environments before entering the operating room.

These technologies represent extraordinary promise. Yet they also carry risks. Without equitable access, they may deepen global health inequalities. If machines become too dominant, they may also distance doctors from the patients whose dignity they are meant to protect. The challenge for future ENT will not only be adopting innovation but ensuring that progress remains humane and inclusive.

A story of resilience and connection

The history of ENT is more than a timeline of instruments and discoveries. It is a reflection of humanity’s struggle to preserve its most intimate connections: the ability to hear a child’s voice, breathe freely, or sing a song. From honey-soaked remedies in ancient Egypt to robotic arms guided by artificial intelligence, the field has been shaped by resilience and ingenuity.

As ENT steps into the era of robotics, nanotech and AI, success will be measured not just by technical sophistication but by fairness, compassion, and accessibility. The future of ENT will depend on whether these extraordinary tools are used to restore not only function but dignity.

The question for the twenty first century is therefore not only what ENT can achieve but who it will serve. Will these advances remain confined to a privileged few, or will they become a universal right to breathe, hear, and speak with dignity?

Reference

Dharmadhikari, V. M., Mungal, S. M., Gaikwad, A. K., Kalakoti, S. P., & Katre, A. S. (2024). The journey of otorhinolaryngology: From past to present and into the future. Indian Journal of Otolaryngology and Head & Neck Surgery. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12070-024-04955-7

Fenster, J. M. (2001). Ether day: the strange tale of America’s greatest medical discovery and the haunted men who made it.