Imagine if the cure for anxiety or depression did not come in a pill bottle, but in a spoonful of yoghurt. For centuries, fermented foods like kefir, sauerkraut and miso have been part of traditional diets. What people did not know then is that these foods are brimming with living microbes that may have a profound influence not only on digestion but also on the brain.

In a review published in Beneficial Microbes, Abrar Hussain and colleagues from the University of Karachi documented this emerging field of psychobiotics, probiotics and prebiotics that interact with the brain through the gut-brain axis and hold promise for the treatment of psychological disorders. Their work adds weight to a growing movement in science that suggests mental health may be deeply connected to the microscopic world inside us.

What is a microbiome?

The human body is home to a vast microbial universe. Collectively called the microbiome, these microbial communities inhabit the gut, skin, mouth and other niches. In fact, microbes outnumber human cells by about ten to one. With nearly 100 trillion microorganisms representing around 1,000 species in the gut, our bodies are more microbial ecosystems than purely human.

When this balance is healthy, a state known as eubiosis, the microbiome supports immunity, metabolism and even social behaviour. When disturbed, a condition called dysbiosis can trigger problems ranging from digestive issues to inflammation, and increasingly, links are being made to mental health. Beneficial species, often referred to as “friendly bacteria,” play crucial roles in preventing disease and producing compounds essential for brain function.

From yoghurt to probiotics

The concept of manipulating gut microbes for better health is not new. In the early 20th century, Nobel laureate Elie Metchnikoff proposed that life could be prolonged by consuming fermented milk containing beneficial bacteria. This idea eventually gave birth to the modern concept of probiotics, formally defined by the World Health Organization and Food and Agriculture Organization in 2002 as “live microorganisms which, when administered in adequate amounts, confer a health benefit to the host.”

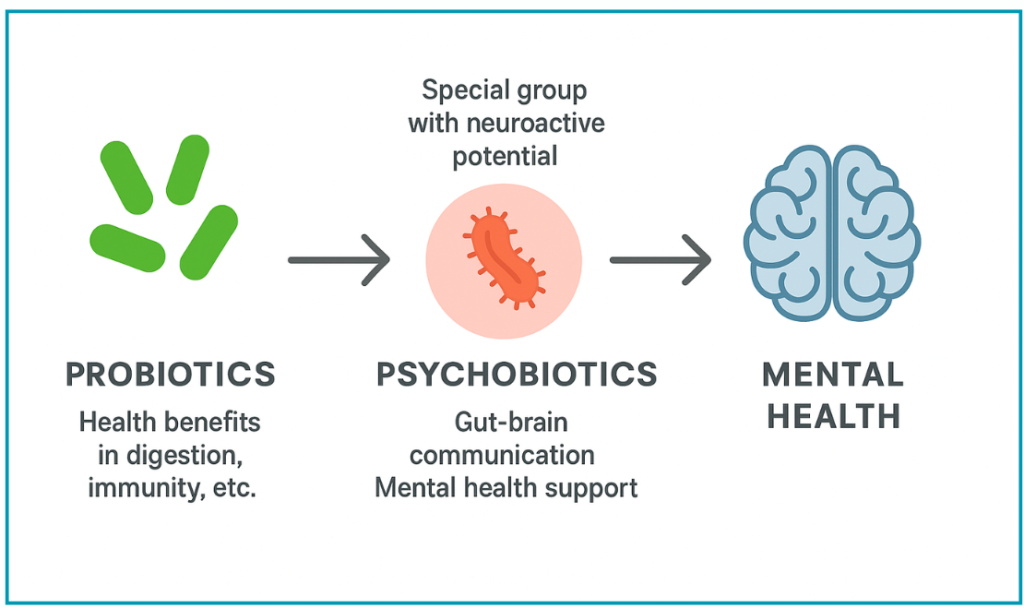

Since then, probiotics have entered the mainstream, shaping billion-dollar industries in health, food and biotechnology. Today, supermarket shelves are lined with drinks and supplements marketed to “balance your gut.” But beyond digestive wellness, researchers like Hussain are investigating how probiotics influence the brain. This new frontier gave rise to the term psychobiotics in 2013, introduced by Timothy Dinan and colleagues.

The rise of psychobiotics

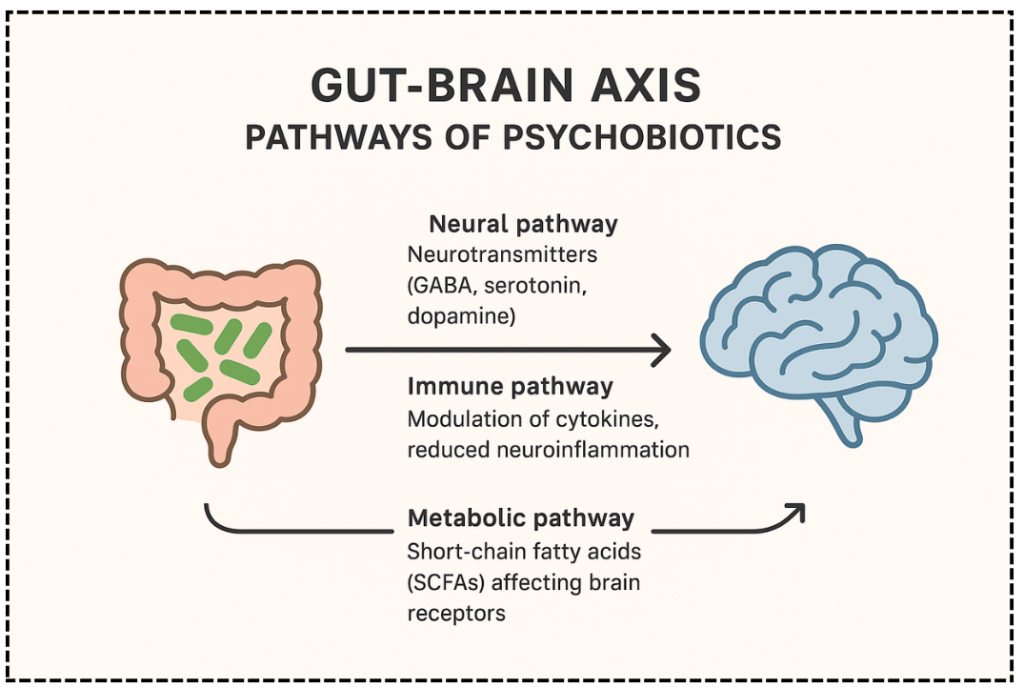

Psychobiotics are probiotics, prebiotics, and other microbiota-targeted interventions that influence the gut-brain axis. This axis is a complex communication network linking the gut to the central nervous system through neural, hormonal, immune and metabolic pathways. By acting on this system, psychobiotics can potentially improve mood, reduce anxiety, enhance memory and even alleviate symptoms of neurodegenerative conditions.

Mental health disorders already affect more than one billion people worldwide, according to the World Health Organization. Conditions such as depression, anxiety, dementia and Parkinson’s disease represent an immense burden both socially and economically. Current treatments whether antidepressants, cognitive therapy or neurological drugs, often come with high costs, limited efficacy or unwanted side effects. Against this backdrop, psychobiotics are being hailed as a possible “green” alternative to traditional therapies.

How gut microbes talk to the brain

The mechanisms by which psychobiotics act are intricate yet fascinating. Gut microbes produce a variety of neuroactive substances, including serotonin, dopamine, gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), acetylcholine and melatonin. These molecules are critical for regulating mood, cognition and sleep.

For instance, when probiotics increase serotonin synthesis in the gut, it influences plasma tryptophan levels, which in turn modulate serotonin production in the brain. Other pathways involve short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) that interact with G-protein coupled receptors, affecting signalling related to psychiatric conditions.

The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, a central stress response system, is also modulated by psychobiotics. In states of chronic stress or illness, the HPA system becomes dysfunctional, leading to elevated stress hormones. Certain probiotic strains can stabilise this system, offering a protective effect. Additionally, postbiotics, metabolic by-products produced by probiotics, alter host metabolism in ways that can benefit brain function.

When microbes go wrong

While many microbes are protective, imbalances can have devastating effects. Research shows that the presence of Alistipes bacteria is associated with stress, while Oscillobacter species are linked to depression. Oscillobacter can produce valerianic acid, a compound that disrupts GABA receptors in the brain and destabilises the delicate balance of excitatory and inhibitory signals.

These insights help explain why dysbiosis has been implicated in conditions such as depression, anxiety and even epilepsy. Understanding these microbial fingerprints could lead to personalised psychobiotics therapies tailored to an individual’s microbiome profile.

Clinical promise and scientific challenges

Despite the excitement, psychobiotics are not yet classified as pharmaceutical drugs. At present they are consumed as dietary supplements, and much remains unknown about the optimal dose, duration and strain-specific effects needed for therapeutic outcomes. Clinical trials have shown promising results in alleviating depression and stress symptoms, but findings are often inconsistent and sometimes limited by small sample sizes.

This gap between laboratory science and clinical application highlights the need for rigorous, large-scale studies.

While psychobiotics may never replace mainstream therapies entirely, they could become valuable complements, especially for people seeking natural or adjunctive approaches.

-Dr. Abrar Hussain

Beyond mental health

The implications of psychobiotics may extend further than psychiatry. Studies are exploring their role in neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s, where inflammation and dysbiosis appear to accelerate disease progression. There is also growing evidence that psychobiotics could support cognitive function in healthy populations, improving focus and reducing stress in everyday life.

As biotechnology advances, psychobiotics might be incorporated into tailored diets or even prescribed as part of personalised medicine strategies. The integration of microbiome analysis with psychiatric care could redefine how doctors’ approach mental health.

The bigger picture

From the University of Karachi, Hussain’s review is helping shape this dialogue. The 2024 review in Beneficial Microbes synthesises global evidence and points to both the opportunities and limitations of this field. By bridging microbiology and psychiatry, psychobiotics illustrate how interconnected human health truly is.

The story of psychobiotics is also part of a broader cultural shift. Mental health is no longer confined to therapy rooms or neurology clinics; it now extends into kitchens, supermarkets and personal lifestyle choices. This makes science communication critical. Public understanding

Conclusion: A spoonful of hope?

The idea that microbes could be allies in tackling the global mental health crisis is both revolutionary and humbling. From yoghurt cups to laboratory cultures, psychobiotics highlight how profoundly life’s smallest organisms can influence its most complex organ, the human brain.

Yet many questions remain. Which strains are most effective? What is the ideal dosage? Can long-term use reshape the brain’s resilience to stress and disease? Science is still searching for definitive answers.

As Abrar Hussain’s article shows, psychobiotics hold extraordinary potential but must be explored with scientific rigour. For now, they represent a tantalising glimpse of a future where mental health care could be supported not only by pharmaceuticals but by the living microbes inside us.

Will the next generation of antidepressants come not from a laboratory, but from our own gut?

Reference

Hussain, A., Koser, N., Aun, S. M., Siddiqui, M. F., Malik, S., & Ali, S. A. (2024). Deciphering the role of probiotics in mental health: A systematic literature review of psychobiotics. Beneficial Microbes, 16(2), 135–156. https://doi.org/10.1163/18762891-bja00053